In the first decade of the twenty-first century, anti-state rebellions were an endemic feature of South Asia’s political landscape. Both separatist and revolutionary insurgencies presented serious challenges in India; Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), also known as the Pakistani Taliban, rose with frightening speed to challenge a long-complacent Pakistani security establishment; Maoist insurgents mobilized against the Nepali government; the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE; “Tamil Tigers”) carved out a de facto state in northern Sri Lanka; and some predicted a rising violent Islamist tide in Bangladesh. In extreme cases, there were fears of partial or total state failure.

Yet by 2020, the state is ascendant in South Asia. Most anti-state revolts across the subcontinent have been crushed, demobilized, or contained. The major insurgencies in India have seen a downward trend in lethal violence; the TTP has been badly degraded; the Tamil Tigers have been destroyed; Nepal’s Maoists have been incorporated into a new Nepali political system; and Bangladesh’s descent into “competitive authoritarianism” has been grimly accompanied by a reduction in direct anti-state violence.1

Governments have established greater control of previously contested territories, deployed new technologies of surveillance, and, in some cases, fused party rule with state coercive power. New forms of state and non-state coercion have become more politically prominent, especially localized mob and vigilante violence, which are often linked to, rather than aimed at, the state and ruling parties. These changes are neither universal nor irreversible: important conflicts persist and continue to exact a severe human cost. Nevertheless, the landscape of political violence in much of the region is strikingly different in 2020 than in years like 2004 or 2010.

How has this transformation occurred? In some cases, it came through bargaining and political accommodation; in others, the raw application of extremely intense violence; in still others, a long and slow process of containment that has led to a relatively low level of violence even without a real resolution of conflict. In general, state coercive capacity across the region has increased, with escalating security force budgets and manpower facilitated by both formal laws and informal practices that give substantial leeway to the state.

This is not a simple story of state capacity, however: coercive power has been deployed in selective ways, including cases in which a state ignores or cooperates with non-state armed groups, from militias to vigilantes. Non-state armed groups can bolster rather than undermine state power.

Crucially, however, this resurgence of state coercive power remains contested: while a new era of powerful states untroubled by internal competitors may have begun, there are reasons to be cautious. First, important insurgencies still continue in the region, even if they are diminished in intensity, while ideologies, inequalities, and forms of resistance persist that can be mobilized against state power. Suppressing violence is not necessarily the same as resolving conflict. Second, interstate politics are shifting in South Asia, opening the possibility of new dynamics of cross-border spillover, proxy warfare, and state sponsorship of armed groups. Third, forms of violence—especially mobs and vigilantism—are on the rise that are dangerous in their own right and that can prove difficult to control even by colluding state and political party forces. Finally, instability in and political exclusion from regimes can foster rebellions, even after long periods of apparent stability.

Challenges and Responses

The first decade of the twenty-first century saw areas of intense violence across the region. India’s government battled ongoing insurgencies in Kashmir, the Naxalite belt in interior India, and the Northeast. In Pakistan, substantial violence in the southern port city of Karachi was joined by a resurgent insurgency in the southwestern province of Balochistan and an extremely bloody rebellion led by the Pakistani Taliban. In Sri Lanka, the Tamil Tigers reached their peak of power between 2002 and 2005. Terrorist attacks hit Bangladesh, including assassinations and coordinated bombings linked to the Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami Bangladesh and other factions. And in Nepal, a Maoist insurgency fought its way into a stalemate with Nepal’s security forces by 2005.

Yet, in 2020, most of these conflicts are either finished or persist at much lower intensity. The last two decades have seen both a dramatic decrease in insurgency-related violence and a noticeable growth in state coercive power.

India

Since 2000, India has faced insurgencies in three geographic areas. The first is in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), where insurgency arose in the late 1980s following a rigged state assembly election and has continued ever since at varying levels of intensity. The second is in India’s Northeast, the site of numerous revolts since the 1950s. The third is a sprawling belt in central and eastern India where various Maoist insurgent groups (known as Naxalites) have been operating for decades.

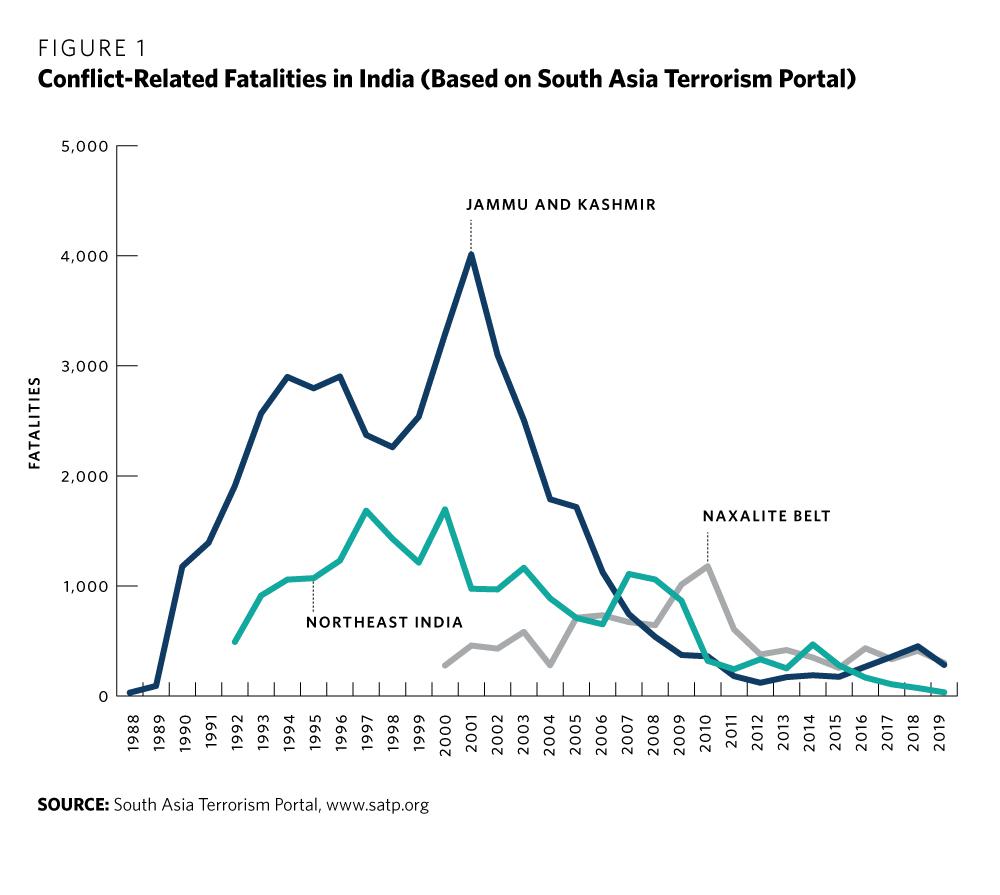

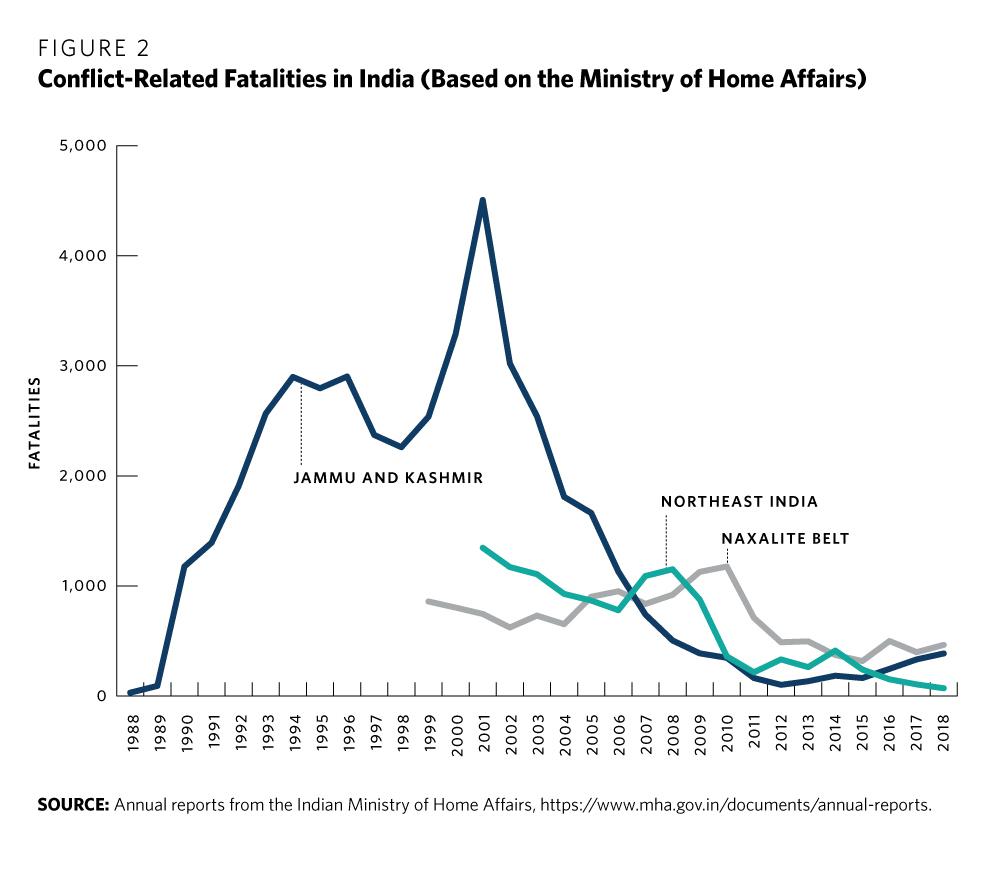

In all of these cases, anti-state violence is now below its twenty-first-century peak. Existing violence data is not adequate to make fine-grained claims: it is likely that official records undercount civilian deaths, and both media and government reports can be highly unreliable in their distinctions between civilians and militants. Furthermore, there is little systematic data on nonfatal human rights violations, such as torture and sexual violence.

As an admittedly crude proxy, however, overall conflict-related fatalities data leaves little doubt about broad trends. Figure 1 below shows fatality data from the nongovernmental South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP), and Figure 2 shows official Indian government data from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA).2

The figures show that in J&K and the Northeast, the late 1990s and early 2000s saw intense conflict. There have been sustained and credible allegations of human rights violations by Indian security forces and various insurgent groups, major disruptions to civilian life, and “mainstream” political systems in these areas requiring heavy force deployments to be sustainable.

In the Northeast, the 1990s saw a resurgence of violence by Naga insurgent factions in Nagaland and neighboring states, the expansion of multiple insurgencies in the state of Assam, and ongoing or new violence in the states of Manipur, Meghalaya, and Tripura. Though there are discrepancies between the MHA and SATP data, both show fatalities in the Northeast holding broadly steady in the first decade of the 2000s, then beginning a sharp drop from 2008 onward. In 2018, there were less than 100 reported conflict-related fatalities, compared to approximately 1,100 in 2008. While the true number of conflict-related fatalities is difficult to ascertain, all indications suggest a sustained and quite dramatic drop in conflict-related fatalities in the Northeast.

The decrease in violence in Kashmir since 2003 is also striking. The reliability of data from this conflict environment is extremely limited: disappearances, dubious claims about the identity of the dead, extensive human rights abuses, and restricted media and NGO access have been characteristics of the last three decades. All that can be credibly inferred is the overall trend, which decreases from the early 2000s to a lower steady state in the 2010s. Unlike in the Northeast, there has been an uptick in conflict-related fatalities in the second half of the decade rather than a continued decrease. The Indian state is absorbing far less damage than in the 1990s or early 2000s, though it retains a costly internal security footprint in the region.

Finally, the Naxalite insurgency gained power and reach between 2004 and 2010, particularly in the Indian states of Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. This triggered a major MHA response combined with the efforts of state police forces, as well as the involvement in some places and times of a controversial progovernment militia. The peak of this conflict’s violence, in 2010, was reached much later than in J&K and the Northeast but has since seen a drop to a consistent but lower level in recent years.

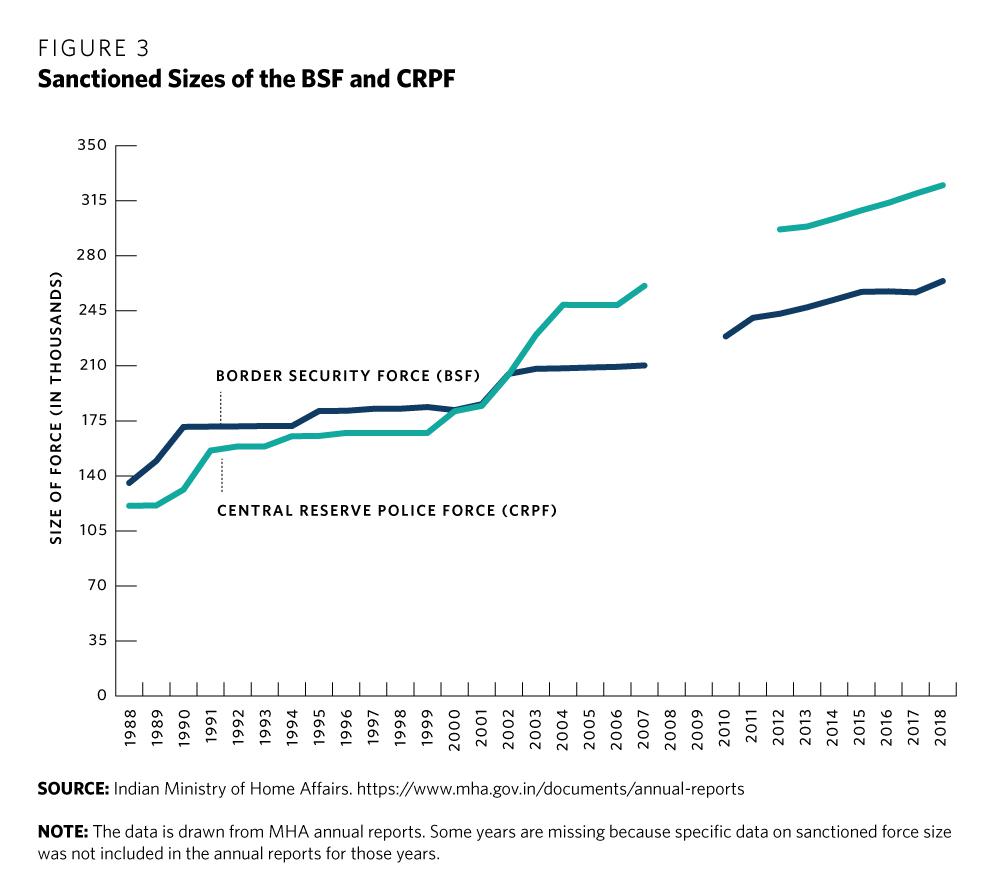

Several factors have worked to reduce insurgent violence against the Indian state. First, there has been a sizable internal security buildup in India over the last two decades. Figure 3 shows the sanctioned strengths of India’s two largest central police forces, the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) and Border Security Force (BSF), from 1988 to 2018.3 The BSF has a major role in J&K, and the CRPF is heavily deployed across India’s areas of insurgency; both have expanded dramatically. The Assam Rifles (AR), a specialized force in the Northeast, has grown much more modestly but still expanded.

MHA expenditures rose an average of 15 percent annually from 2011–2012 to 2020–2021, with expenditures for police specifically rising 12 percent annually on average. The Indian Army also has an important presence in J&K and the Northeast, contributing to a vast security footprint that can suppress insurgent violence. State police forces have been built up in conflict areas, fueled in part by infusions of resources from the central government. The legal system grants substantial latitude to internal security forces, which limits checks on state power, and informal practices add to this autonomy.

The second factor in reducing insurgent violence has been India’s effective use of ceasefires, demobilization deals, and amnesties in the Northeast to peel off and demobilize insurgent factions. While there is a heavy security force presence in the region, there has also been space for long-running ceasefires and negotiations that reduce violence even when they do not fully resolve contested political issues. The Northeast is also the site of India’s most successful peace deals in internal conflicts.

Third, the international environment has changed in the last fifteen years. India and the international community have put sustained pressure on Pakistan to reduce its support for militants and terrorists. Bangladesh provided support for insurgents in the past, but the Awami League government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been fairly friendly to India. India has also improved cooperation with the military in Myanmar, aiming to limit cross-border movements. Chinese support for insurgents in the Northeast, meanwhile, dropped off dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. Although reports of some degree of sanctuary in China and possible tacit support for rebels have grown in recent years, there has not been a return to the levels of the past.

There is not a clear partisan dynamic in these changes. While advocates of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government have heralded his strength and resolve, the trends in insurgent violence under the second Congress Party-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government (2009–2014) look almost identical to those in the Modi government. The same is true of the internal security buildup, both in terms of funding and MHA force sizes, as well as the policies toward both the Northeast and Naxalite-influenced areas. It is in Kashmir where the Modi government has most dramatically shifted policy by revoking the autonomy of and bifurcating the state of Jammu and Kashmir, accompanied by a massive crackdown on movement, communication, and political activity. This was an unambiguously ideological policy by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government, cloaked in claims about development and political renewal that have yet to come to fruition. Nevertheless, a heavy footprint and intensive counterinsurgency have been par for the course in Kashmir for decades.

Pakistan

The dramatic rise of anti-state revolt led by the TTP in Pakistan in the late 2000s left tens of thousands dead and violently challenged the military establishment in ways unseen since the 1971 war that led to the formation of Bangladesh. Fears of Pakistan’s collapse and rise of a revolutionary Islamist project drove international efforts to bolster state counterinsurgency capacity. At the same time, violence in Karachi, insurgency in Balochistan, and sectarian militia activities added further layers of violence to Pakistan’s political landscape.

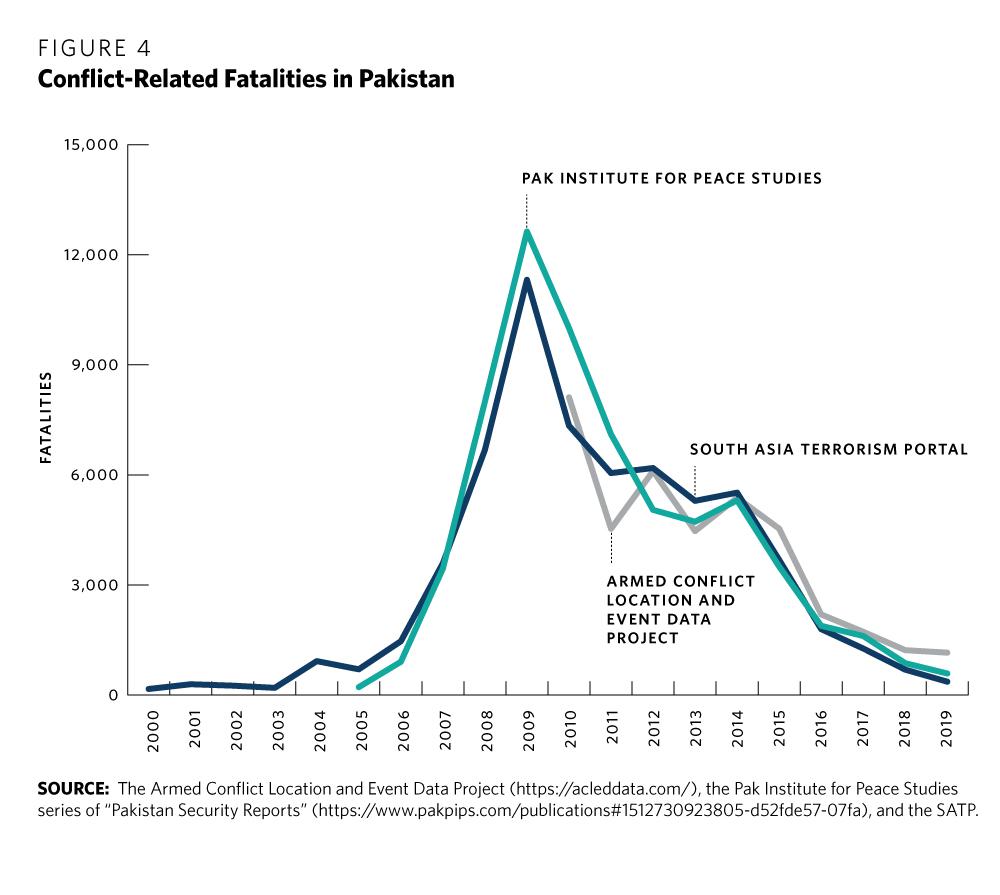

There has been a dramatic transformation of Pakistan’s security environment since the height of the TTP’s power. Figure 4 draws on three datasets on political violence in Pakistan over time.4 While they examine somewhat different definitions of violence, and all of the crucial caveats about data quality outlined above for India hold for Pakistan as well, the basic trend of sharply decreasing fatalities in political violence over the last decade is consistent across them.

The TTP was badly damaged by escalating military crackdowns between 2009 and 2014, most dramatically in the 2014 Zarb-e-Azb offensive. The group has since splintered, with cadres retreating into Afghanistan, abandoning the fight, or lying low. While it has not disappeared and still has the potential for a major resurgence, there has been a dramatic fall from its high point of influence.

A set of deals with local warlords and TTP splinters created partners for the security forces; rather than monopolizing violence, the security apparatus has used other non-state armed groups as tools of power projection and local control. This campaign did not follow classical counterinsurgency best practices; instead, the Pakistani military’s suppression of the TTP saw high levels of state violence, refugee displacement, disappearances, and expansive surveillance.

Having beaten back this challenge, the Pakistan Army has emerged as an even more influential force. The fact that much of the Islamist militancy Pakistan has faced in recent years in part arose from the security establishment’s own past policies has not reduced the military’s heralding of its successes against the TTP.

Another major source of political violence in Pakistan was militarized electoral competition in Karachi, where the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM)—an armed political party with a strong base among ethnic Muhajirs—had been a crucial presence in the city since the 1980s. Over time, it had both clashed and cooperated with both military and civilian governments. Karachi’s politics and political economy involved substantial lethal violence, as well as intimidation and threats. The security establishment, which had a tumultuous relationship with the MQM for decades, launched a crackdown in 2013 that has badly degraded the party, opening space for electoral competitors and reducing electoral violence. As in the mountainous peripheries where the state waged counterinsurgency against the TTP, due process and rule of law have been troubled in the Karachi operations.

Finally, an insurgency grinds on in Balochistan, where a welter of Baloch rebels fights in an area of growing strategic and resource importance, including a Chinese presence linked to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This conflict, which experienced a resurgence in 2005, has not gone away and continues to be politically important. Yet violence appears to have declined, with the caveat that security force operations are opaque. The forces pursued a grim counterinsurgency policy: extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and a heavy security footprint coupled with surveillance and monitoring. The Baloch revolt is likely to endure, as the security establishment has not created a self-sustaining pro-state political order, but it does not currently pose a severe threat to state power.

None of this implies that the military has monopolized violence. Anti-India armed groups are alleged to still operate on Pakistani soil, the Afghan Taliban has consistently used sanctuary along the Afghan border, and localized armed actors have worked with the state in counterinsurgency zones. Depending on where the state has perceived threats and where armed groups have been willing to work with it, there have been dramatically different landscapes of violence.

This blend of repression and collusion has reduced direct anti-state violence. There has been less political accommodation than in India’s Northeast, and human rights abuses are pervasive, fusing counterinsurgency with the broader political objectives of the military in managing Pakistan’s political sphere. All of the active conflict zones remain potential areas of resurgence (for instance, the TTP has been trying to re-consolidate), but, compared to a decade ago, Pakistan’s security establishment has achieved a major shift in the balance of forces.

Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka

In the first decade of the 2000s, both Nepal and Sri Lanka grappled with major insurgencies. The Communist Party of Nepal–Maoist (CPN-M) launched a revolutionary insurgency in 1996, seeking to overthrow the government and create a communist state in Nepal. As Nepal’s government went through extraordinary tumult in the early 2000s, the Maoists expanded their reach and fought the state to a standstill. Yet a peace process emerged that eventually led to the CPN-M’s demobilization and the Maoists’ incorporation into mainstream electoral politics. This has not been a seamless process, and there have been various forms of political violence and conflict since the end of the civil war, but the war has nevertheless decisively ended.

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam insurgency in Sri Lanka has also decisively ended, though in far bloodier fashion. Tamil militancy had been a fact of life in Sri Lanka since the 1970s, with the LTTE coming to dominate the insurgency. From 2002 to 2006, there was a ceasefire before brief, ill-fated negotiations that collapsed back into pitched warfare. From 2006 to 2009, government forces and the LTTE waged an extremely intense, mostly conventional conflict with extensive human rights abuses. The LTTE was finally defeated, at a huge civilian cost, in 2009. Since then, other than the Easter bombings by an Islamist cell in 2019, there have not been major acts of anti-state violence. Instead, mob violence has become a more persistent concern than rebellion. Nevertheless, a large security presence has been established in Tamil areas, justified by the specter of resurgent revolt, and state forces have not been held accountable for past human rights abuses.

Finally, Bangladesh has become a de facto “competitive authoritarian” regime in which the ruling Awami League established a dominant position. Unlike in the other countries examined here, large-scale anti-state insurgency has not been a major feature of Bangladesh’s politics in the last two decades; a 1997 peace deal with the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti, a political party formed to represent the Indigenous peoples in the eastern Chittagong Hill Tracts, marked the end of a classical insurgency. Islamist cells have launched dramatic terror attacks but, especially since 2016, these were met with intense repression and have decreased in frequency. Political violence is instead much more likely to emerge from clashes between political parties or, above all, from the state itself as the security apparatus is used to buttress Sheikh Hasina’s rule.

Legacies and Tensions

These changes across South Asia may be permanent, heralding the dominance of the state after a long period of persistent insurgent challenges. The growing size and resources of internal security forces, consolidation of powerful regimes, and changed international environment may have made rebellion increasingly unsustainable, even when political grievances remain.

Yet there are reasons to be cautious in concluding that there has been an irreversible transformation. The countries of South Asia are incredibly diverse, so there are no simple takeaways from these trends. For instance, Nepal’s peace process is a model of civil war termination through a political settlement, while the Sri Lanka government’s destruction of the LTTE left a trail of dead and displaced civilians.

Despite this heterogeneity, several possible sources of recurring insurgency can be identified, even in an era of increased state power.

First, violence suppression is not the same as conflict resolution. There is a fundamental difference between a context in which security forces are targeted (even with only rare success) and those in which no one is interested in attacking the state. India and Pakistan continue to heavily garrison areas of insurgency, regardless of violence levels. These simmering conflicts can always increase in intensity if underlying political conflicts endure. In a number of cases, a self-sustaining, pro-state political order remains distant, and the security apparatus is instead needed to deter or contain resistance.

Second, the increasingly volatile international politics of the region may provide new incentives for governments to support armed groups across borders, tapping into preexisting conflicts and grievances. For example, the TTP is alleged to be regrouping in Afghanistan, Pakistan claims that India is supporting Baloch rebels, the Taliban operates out of Pakistan, India focuses on Pakistan’s long history of support for terrorist and militant groups, and Indian media signals concern about Chinese backing for insurgents in the Northeast. This unpredictability makes it at least conceivable that there could be renewed efforts by states to support rebellions in strategic areas.

Third, even noninsurgent violence has the potential to spiral into broader conflict. In India and Sri Lanka, mob violence and vigilantism have occurred with the connivance or tacit neglect of leading political parties. Such non-state violence is often not waged against the state or political system, but instead is used as a bloody tool of social control and political maneuvering. Yet as Sri Lanka’s experience in the 1950s and 1980s vividly suggests, mob violence can harden political cleavages and trigger escalation beyond the control of its political patrons.

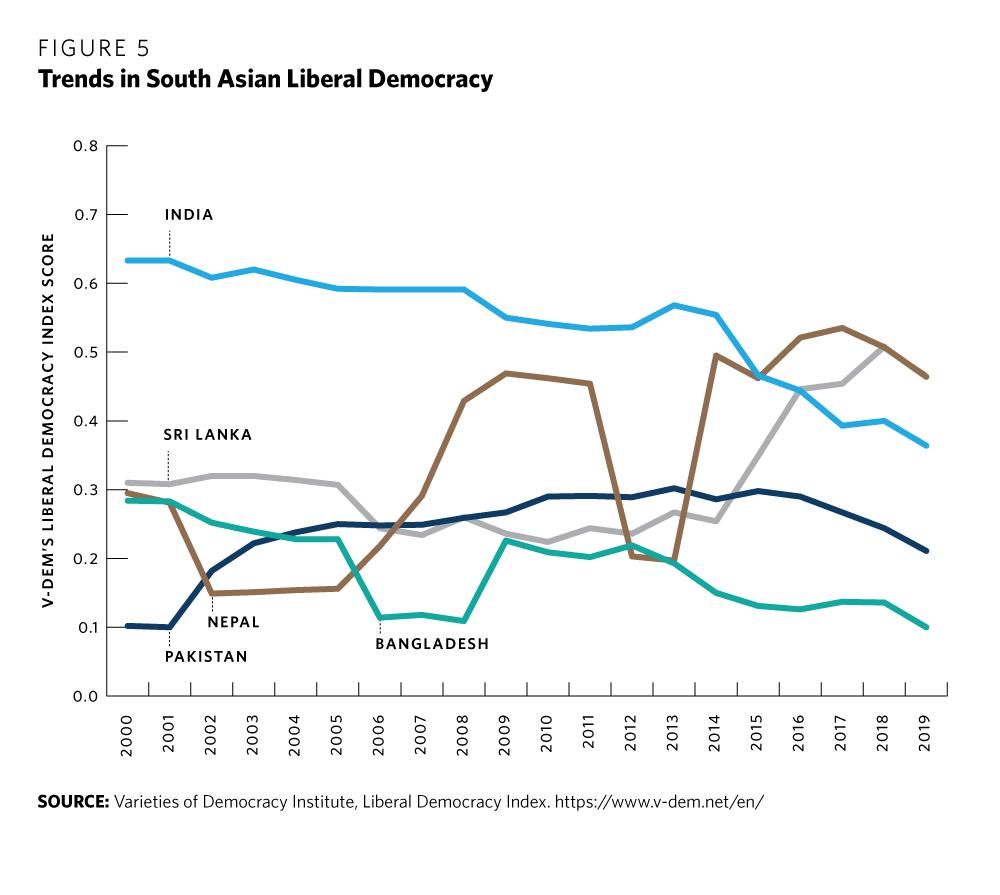

Finally, domestic political instability can provide both opportunity and motivation for insurgency. In the region’s largest states, rather than reductions in violence opening space for revitalized democracy, there has been democratic decay or stagnation. Figure 5 shows trends in V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy index since 2000 (higher numbers indicate greater liberal democracy). India, once the exceptional case of liberal democracy in the region, has seen its rating drop in recent years, echoing a decrease in Freedom House’s assessment. Pakistan’s counterinsurgency successes have been accompanied by the military’s enduring political power and serious limits on rights. In Bangladesh, regime repression of dissent and of opposition movements have been commonplace. In Sri Lanka, the period of victory over the LTTE and its aftermath saw autocratization under the rule of the Rajapaksa family, a trend that changed when a new government came to power in 2015. The implications of the return of the Rajapaksas in 2019 (Gotabaya as president and his brother Mahinda as prime minister) remain to be seen. Finally, Nepal has meaningfully improved its democratic practice since the end of its civil war.

These trajectories matter because political exclusion and partial democracies marked by factionalism can contribute to revolt, especially when combined with a potentially more volatile international environment. In Bangladesh, the highly personalized Awami League uses the security forces as a tool of regime survival. Breakdown or factionalization within the regime could trigger intense instability. While the Pakistani military is currently riding high politically, its track record over time has included miscalculation and counterproductive policies (for instance, repressing unarmed political movements while tolerating Islamist armed groups that later grew out of control). Moreover, shifts in civilian power and civil-military coalitions are likely to occur in the future, with unpredictable results. India’s coercive apparatus, meanwhile, is vast and growing, but ideological hubris and political exclusion risk backlash.

Conclusion

The political landscape of South Asia has changed dramatically in the last two decades. The state is resurgent, and insurgencies have been eliminated or contained. This is a hugely important shift. Yet extrapolating confidently from this trend is dangerous: the politics of the region are too dynamic to assume continuity. While the growing dominance of state power may become a new, enduring status quo, analysts should pay careful attention to potential triggers of new or renewed revolt.

Notes

1 On the edges of South Asia, Myanmar sees a broadly similar pattern—though important insurgencies continue, a patchwork project of ceasefires combined with ongoing state repression has forged a degree of ugly stability in areas of enduring conflict. The main exception to this pattern is Afghanistan, where violence and full-scale civil war continue. This article focuses on the core states of the Indian subcontinent.

2 Both can be accessed at https://satp.org/. MHA data can also be found in its annual reports (https://www.mha.gov.in/documents/annual-reports) and, for the Northeast, on the North East Division’s website (https://www.mha.gov.in/division_of_mha/north-east-division).

3 These data are drawn from MHA annual reports. Some years are missing because specific data on sanctioned force size was not included in the annual reports for those years.

4 These three sources are the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (https://acleddata.com/), the Pak Institute for Peace Studies series of “Pakistan Security Reports” (https://www.pakpips.com/publications#1512730923805-d52fde57-07fa), and the SATP (see above).