Advertisement

Party strategists pay a lot of attention to redrawing district maps — and hope you won’t bother to think about it.

Mr. Edsall contributes a weekly column from Washington, D.C. on politics, demographics and inequality.

Some of the most important developments in politics do not happen every election cycle, but every ten years, when politicians scrap the old battleground map and struggle to replace it with a new one more favorable to their interests.

Steven Hill, a former fellow at New America, described how this works in his still pertinent 2003 book “Fixing Elections: The Failure of America’s Winner Take All Politics.”

“Beginning in early 2001, a great tragedy occurred in American politics,” Hill wrote. As a result of that tragedy, “most voters had their vote rendered nearly meaningless, almost as if it had been stolen from them” as “hallowed notions such as ‘no taxation without representation’ and ‘one person, one vote’ have been drained of their vitality, reduced to empty slogans.”

Hill was referring to “the process of redistricting” that he argued was legalized “theft” engaged in by “the two major political parties, their incumbents, and their consultants,” which Hill said was “part of the everyday give-and-take (mostly take) of America’s winner-take-all politics.”

Hill first made his argument at a time when both parties were still colluding in developing new districts designed to protect incumbents, Republicans and Democrats alike. Since then, the parties have abandoned any semblance of bipartisanship and are now fully engaged in an all-out battle for control of state legislatures.

A basic objective remains the same, however: to effectively disenfranchise key segments of the electorate.

As Devin Caughey, a political scientist at M.I.T. and the lead author of “Partisan Gerrymandering and the Political Process,” explained in an email:

The goal of partisan gerrymandering is to maximize one party’s seat share given their vote share. The means to this end is drawing districts that waste as many votes for the opposing party as possible, while wasting as few votes as possible for one’s own party.

In addition to creating wasted votes — thus undermining a key principle of democracy — an additional consequence of gerrymandering is what Nicholas Stephanopoulos of Harvard Law School calls “representational distortion”: the adoption of policies that do not have majority support in the electorate.

Stephanopoulos, the author of the 2018 paper “The Causes and Consequences of Gerrymandering,” described “one glaring example,” in an email:

Democrats got more votes than Republicans in the 2012 and 2018 Wisconsin state legislative elections. So in a world without gerrymandering, Democrats would have been able to block all kinds of conservative policies between 2012 and 2014, including environmental deregulation, tax cuts, abortion restrictions, gun deregulation, etc.

Instead, Republican majorities in both branches of the Wisconsin legislature enacted all of those policies, as well as a package of anti-union measures.

In the 2018 election, Democrats won 53 percent of all votes cast in the Wisconsin State Assembly contests, but won 36 percent of the State Assembly seats.

In his paper, Stephanopoulos wrote:

What is undeniably a democratic malfunction, though, is representation that does not reflect the ideological preferences of the electorate — representation that is much more liberal or much more conservative than voters actually want.

His conclusion?

Single-party control of redistricting fosters partisan unfairness more than any other variable, and that such unfairness translates directly into ideologically distorted representation.

Caughey is also concerned about gerrymandering because it leads to a denial of political representation of the majority electorate:

Our basic point about distortion of representation is that partisan gerrymandering pulls state policies in the ideological direction of the party that controls redistricting. This policy effect follows from two facts: (1) gerrymandering allows one party to capture more seats than it would otherwise control, and (2) the occupants of the extra seats vote very differently from the members of the opposite party who would otherwise have occupied those seats.

Since the party in power can “skew policies toward its preferences,” Caughey continues, “the policy effects of additional seats are greatest when party control hangs in the balance. Thus, gerrymandering is most consequential when it gives one party a majority of seats when it would otherwise have a minority.”

Richard Pildes, a law professor at N.Y.U. and an outspoken critic of distorted legislative districts, wrote in an email:

Gerrymandering is antithetical to democracy; politicians should have to compete for popular support under neutral, fair rules of engagement — rather than being able to manipulate the playing field to entrench themselves and their allies in power.

Pildes argues that gerrymandering is

about as pure an example as we have of insiders rigging the system for their own benefit. It also poisons state legislatures, when the decade begins with one party ramming down the throat of the other a manipulative map that affects the state for a decade.

The fight to control redistricting next year is taking place in relatively low visibility races for legislative seats in states ranging from Kansas to Texas to Minnesota.

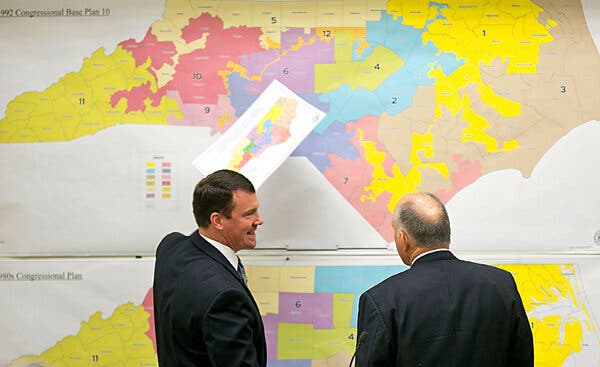

The Princeton Election Consortium has produced a detailed analysis of those elections in six states, Texas, Minnesota, Connecticut, Kansas, Florida and North Carolina. The consortium, which is headed by Sam Wang, a professor of neuroscience at Princeton, identifies the key “races where voters have the most leverage to prevent partisan gerrymandering in 2021. A few hundred voters mobilized in the right districts could bring bipartisan control of redistricting to a state, leading to fairer districts for a decade.”

The consortium found, for example, that a cluster of eight Kansas state house districts in Johnson County, an affluent suburb of Kansas City, offers key opportunities for Democratic voters and donors to shift the balance of power statewide.

In a reflection of partisan enthusiasm, in 2019, the first full year of the current election cycle, Johnson County Democrats outraised Johnson County Republicans $108,314 to $58,480.

In North Carolina, the consortium identified three districts in the Highpoint-Greensboro-Winston Salem region as strong targets for Democrats seeking to wrest control of the North Carolina house.

Gerrymandering battlegrounds vary widely, both in terms of the parties’ goals and strategies.

In Kansas, for example, where Republicans overwhelmingly dominate both branches of the legislature, the Democratic goal is to pick up just one more seat in the Kansas House. That would give the party enough votes to block a Republican gerrymander by preventing the Republican majority from overriding a veto by the Democratic governor of a Republican redistricting plan. In other words, without veto-proof majorities in both branches, Republicans would be forced to work with Democrats in drawing both legislative and congressional district lines.

In Minnesota, the Democratic goal is to gain a State Senate majority by winning at least two additional seats. If successful, Democrats would then have complete control over redistricting — a so-called trifecta — the governor, the State Senate and the state House, with Republicans left powerless.

Republicans currently have trifectas in 21 states, Democrats in 15 — the remaining states have divided government. Fourteen states, including California, Ohio and Michigan, have shifted control over redistricting from the state legislature to an independent commission. Eleven others use independent commissions either to advise legislatures or to step in when no agreement can be reached. Republicans control both branches of the legislature in 29 states to the Democrats 19, with the only split in Minnesota. (Nebraska’s state government is unicameral.)

For partisans engaged in state legislative battles, anti-democratic concerns over gerrymandering fall on largely deaf ears — these activists are forced by the rules of the game to compete in redistricting contests because the stakes are so high.

Take the issue of voting rights and the sustained efforts by Republicans to suppress turnout, especially among pro-Democratic minorities.

Richard Hasen, a professor of law and political science at the University of California-Irvine, wrote by email:

The trend at the Supreme Court and in the lower courts, increasingly stacked with Trump appointees, is a pullback on federal protection of voting rights. That means that many voting rights struggles will begin and end with what state legislatures — and in some cases state supreme courts applying state constitutions — say the rules will be.

Fredrick Cornelius Harris, a professor of political science and director of the Center on African-American Politics and Society at Columbia, warned that current developments — the likely census undercount of minorities and the poor and the Trump administration’s discouragement of immigrants from filling out census forms, together with the Covid-19 pandemic — will weaken the political leverage of minorities post-2021 redistricting.

These factors, Harris wrote by email, “could impact the reapportionment of seats in state legislatures,” before adding that

A weakened voting rights act — this will be the first reapportionment since Shelby County vs. Holder — could have an impact on the number of majority-minority districts in the South. Since Republicans run state houses in the Deep South, there can be a potential loss of seats for Democrats and Black/Latino legislators in some of those states if Republicans choose to do so.

In many of the key states where state legislative contests are fought most intensely, Democrats are generally on offense and Republican on defense. A major factor driving this difference is the continuing suburban animosity toward Trump that is pushing many independents and nominally Republican voters toward the Democratic Party, as the 2018 election demonstrated.

This pattern of Republican vulnerability has proved especially true in Texas, where Democrats are determined to capitalize on the major gains they have made in state and federal contests in the suburbs of Dallas, Houston and other cities.

Robert M. Stein, a political scientist at Rice University who has been closely following contests in Texas where Democrats need to gain nine seats to take control of the state house, wrote me:

The polling I am seeing and expect to see in the next few weeks suggests the Democrats have a better than even chance — 55 percent likelihood — of picking up more than nine seats.

In addition, Stein wrote,

the registration numbers are moving away from the Republicans’ previous 1 million voter advantage. Since 2017, 5 percent more Democrats registered to vote in Texas than Republicans and this advantage appears to be widening since the first of the year. The demographic shift is bearing fruit for Texas Democrats and in a predictable fashion.

In the national fund-raising competition, the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee is slightly behind the Republican State Leadership Committee for the period from January 1, 2019 through June 30, 2020, according to I.R.S. records, $28.1 million to $32.8 million.

These figures do not, however, take into account the surge in support of other Democratic groups involved in state legislative contests. The most important of these is the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, headed by former Attorney General Eric Holder, which has raised more than $50 million since its founding in 2017. The committee backs Democratic legislative candidates but requires them to support efforts to restrict gerrymandering, including the creation of independent redistricting commissions.

While Democrats are on the offensive, especially in suburban legislative seats across the county, the party is fighting an uphill battle overall.

Charles Nuttycombe, director of CNalysis, an election forecasting firm, assessed the likely outcomes of state legislative races in “The State of the States: The Legislatures,” an essay published at Crystal Ball, the political website run by Larry Sabato, a political scientist at the University of Virginia. Nuttycombe’s conclusion is best summarized in the sub-headline: “Don’t expect much overall change even as many chambers are competitive.”

One of the major problems Democrats face is the unexpected resilience of a $30 million 2010 Republican program called Redmap — the Redistricting Majority Project. This exceptionally successful initiative was developed by Ed Gillespie and Karl Rove, who recognized the crucial role of state legislatures in determining the balance of power in Congress.

As Reuters reported, in the 2010 election, the Republican Redmap project

netted some 700 state seats, increasing its share of state House and Senate seats by almost 10 percent, from approximately 3200 to over 3900. It took over both legislative chambers in 25 states and won total control of 21 states (legislature and governorship) — the greatest such victory since 1928.

Christopher Warshaw, a political scientist at George Washington University, is a co-author with Devin Caughey and Chris Tausanovitch, a political scientist at U.C.L.A., of “Partisan Gerrymandering and the Political Process,” which I mentioned earlier. Warshaw emailed me about the continued success of Redmap:

It’s really remarkable how extreme and durable some of the gerrymanders from 2011-12 have been. A number of studies have shown that the Republican gerrymanders in places like Michigan, Ohio, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin were among the most extreme in history. In Congress, these gerrymandered maps probably gained Republicans at least a dozen seats. One study recently estimated that Republicans gained 27 seats in Congress from the 2011 maps.

In the case of Michigan, North Carolina and Wisconsin, Warshaw pointed out,

Republicans have continued to control the majority of seats year after year in both chambers of the state legislatures. This is despite the fact that Democrats received a majority of the votes in state legislative elections in all three states in 2018. In some of these states, Democrats would probably need to win the popular vote by more than 10 percent to win control of the state legislature. So while I do think that Democrats will win control of a couple more chambers in 2020 if Biden continues to have an 8+ point lead over President Trump, it’s going to be very difficult for Democrats to overcome the Republican gerrymanders in places like Michigan, North Carolina, and Wisconsin.

In other words, Democrats may have the wind at their backs this year, but the roadblocks Republicans have constructed over the course of the past decade are quite likely to prove insurmountable, for quite some time, no matter which party takes the White House, no matter how meaningless voters find the ballots they cast and no matter how many American voters are deprived of a voice.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.