Advertisement

Mayors have limited control over problems that many Republicans have walked away from.

Minneapolis, Chicago, Portland, Ore., and Kenosha, Wis., are first and foremost “Democrat cities” in President Trump’s telling. They have Democratic mayors, Democratic policies, Democratic turmoil.

With this refrain, Mr. Trump has sharpened his party’s long-running antipathy toward urban America into a more specific argument for the final two months of the campaign: Cities have problems, and Democrats run them. Therefore, you don’t want Democrats running the country, either.

But that logic misconstrues the nature of challenges that cities face, and the power of mayors of any party to solve them, political scientists say. And it twists a key fact of political history: If cities have become synonymous with Democratic politics today, that is true in part because Republicans have largely given up on them.

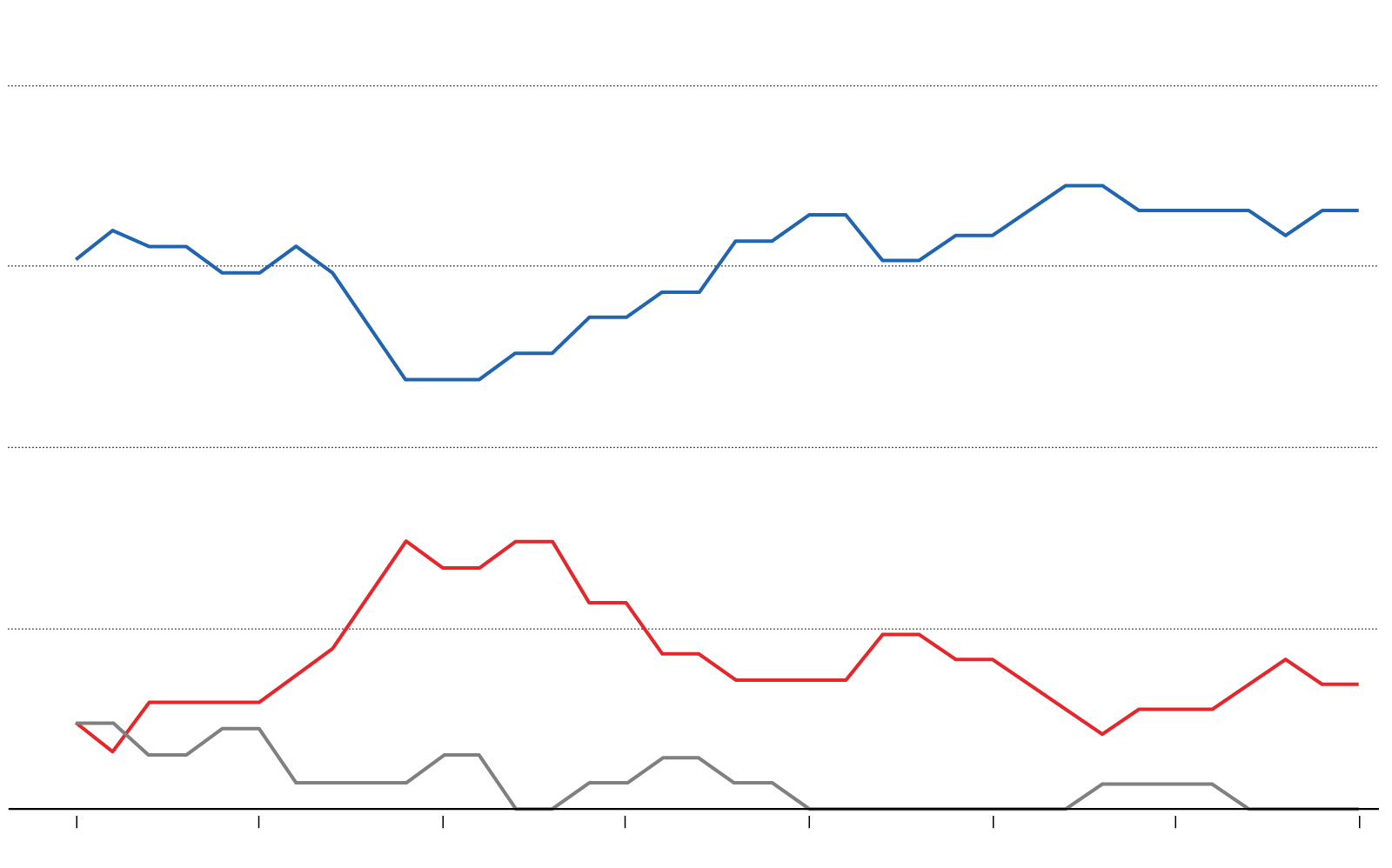

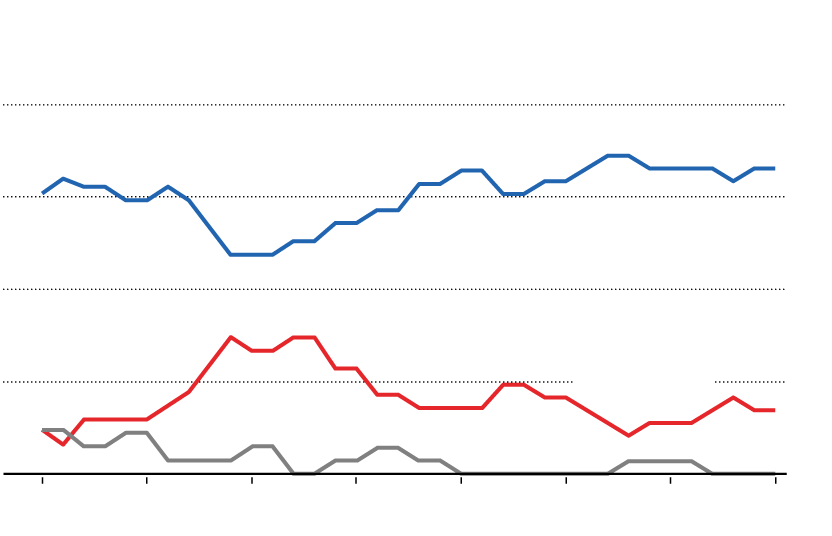

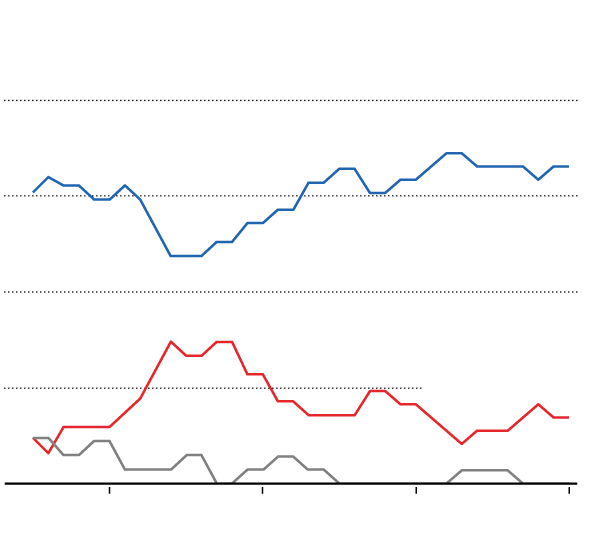

Over the course of decades, Republicans ceased competing seriously for urban voters in presidential elections and representing them in Congress. Republican big-city mayors became rare. And along the way, the Republican Party nationally has grown muted on possible solutions to violence, inequality, poverty and segregation in cities.

Share of

Mayors

Democratic

Republican

Other/Unknown

Share of

Mayors

Democratic

Republican

Other/Unknown

Share of

Mayors

Democratic

Republican

Other/Unknown

Note: In cities with over 500,000 residents. The partisanship of mayors running in non-partisan elections was identified by local news reports, other offices held by the candidate and campaign donation data. Source: Justin de Benedictis-Kessner and Christopher Warshaw

Mr. Trump and his surrogates have pushed that history to its seeming conclusion: Rural and suburban problems in America today are national problems — but urban problems are Democratic problems.

“A lot of those critiques are pretty cynical,” said Thomas Ogorzalek, a political scientist at Northwestern University. “They’re saying: ‘You can’t solve these problems, so you’re bad at governance. And we’re not interested in solving these problems. We’re going to stay out of that conversation until it gives us a partisan opportunity to win someplace else.’”

That partisan opportunity has arisen in Kenosha, where the president traveled on Tuesday as he has sought to turn the attention of voters toward issues of law and order. Some residents of Kenosha have expressed alarm at how local Democratic officials have handled the unrest there. But the president did not offer his own vision for easing police-community tensions, or for addressing the roots of violence. Instead, he used the setting to indict “reckless far-left politicians.”

The argument has few parallels in American politics. Politicians, of either party, do not blame Republican county executives for rural opioid problems. Nor do Democratic mayors get credit for a quarter-century decline in urban crime that began in the early 1990s, greatly improving safety in many cities.

In reality, mayors alone wield limited control over crime rates. Several researchers could point to no studies suggesting that the partisanship of a mayor has an effect on this. And while homicides have spiked this year in big cities, they have risen by similar amounts in a number of smaller cities with Republican mayors, including Tulsa, Okla., and San Bernardino, Calif.

The president, however, has never mentioned these places — or Republican-led Miami, Jacksonville, Fla., or Fort Worth — in his vows to deploy federal forces to help control urban crime.

Numerous studies suggest that the partisanship of mayors has limited effect on much of anything: not just crime, but also tax policy, social policy and economic outcomes.

The researchers Justin de Benedictis-Kessner and Christopher Warshaw have found that Democratic mayors spend more than Republican mayors. “But the differences are pretty small,” said Mr. Warshaw, a political scientist at George Washington University. “They’re not enough to drive large differences in societal outcomes in things like crime rates.”

This is partly because mayors are constrained in their ability to execute ideological agendas. Cities can’t run deficits. States limit their authority to raise taxes and enact laws on many issues. And cities lack the power the federal government has to shape labor laws, or immigration policies that can affect their population growth.

The president has effectively ascribed a level of power to mayors that they simply do not have.

“The assumption is that cities are city-states,” said Joshua Sapotichne, a political scientist at Michigan State University. “What that means is that they have the autonomy to act on the preferences of their constituents. And that’s not even true with respect to social distancing, mask mandates and lockdowns on the Covid side.”

The president has harshly criticized Chicago for failing to control gun violence. But in the past the city took relatively severe policy responses, outlawing handguns and gun sales. Federal judges overturned those efforts, making clear again how constrained local officials are.

“Democratic mayors don’t govern as Democrats for the most part,” said Elisabeth Gerber, a political scientist at the University of Michigan.

The Massachusetts election went smoothly, but its harsh deadlines may have disenfranchised some voters.

Sept. 2, 2020, 5:36 p.m. ET

Trump and Biden will both visit Shanksville, Pa., on Sept. 11.

Sept. 2, 2020, 5:02 p.m. ET

Navajo Nation asks a court to allow ballots postmarked by Election Day to be counted.