By Theodore R. Johnson

With posters by Kennedy Prints

In the autumn of 2008, just a few weeks after my 33rd birthday, I cast a ballot for the first time. Up to that point, serving in the military seemed like more than sufficient civic engagement and provided a ready excuse for voluntarily opting out of several elections. By the time Barack Obama won the Democratic primary, I was an officer who’d spent more than a decade in the Navy and not a second in a voting booth. This apathy does not run in the blood. My parents are products of the civil rights era and the Jim Crow South, and as such religiously exercised their hard-won right to vote. In my formative years, the basic disposition of the house politics pressed together progressive demands for racial equality with the Black conservatism of marathon church services that stretched deep into Southern Sunday afternoons. We differed in degree on any number of issues, but elections were where our politics really diverged. Like much of Black America, my mother is a lifelong Democrat, staying true even as the party vacillated in and out of her good graces. My father is a somewhat perfunctory Republican, an heirloom affiliation inherited from Black Americans’ early-20th-century preference for the party of Lincoln and consecrated in the familial name carried by my grandfather, father and me: Theodore Roosevelt Johnson.

But in November 2008, all three of us checked the box for Obama, our votes helping deliver North Carolina to a Democratic presidential nominee for only the second time in 40 years. My father had crossed party lines once before, in 1984, when Jesse Jackson ran for president. Jackson’s business-size Afro, jet black mustache and Carolina preacher’s staccato cadence transformed the typically all-white affair of presidential contests. “If a Black man had the opportunity to sit in the Oval Office,” my father told me years later, “I wasn’t going to sit on the sidelines.”

Listen to This Article

Audio Recording by Audm

To hear more audio stories from publishers like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android.

Jackson championed a policy agenda nowhere close to my father’s conservatism. But his rationale for supporting Jackson hinged on a basic proposition, informed by generations of Black experience in America: The thousands of lesser decisions made in rooms of power can matter far more for racial equality than campaign promises and platforms. Senator Kamala Harris crisply captured this sentiment while campaigning last year, declaring a simple truth: “It matters who’s in those rooms.” My rationale for voting for the first time was much like my father’s two decades earlier. I was not going to stand idly by if there was a chance to put a Black man in those rooms.

On the surface, my family’s choices may seem unremarkable. As David Carlin wrote in the Catholic magazine Crisis, weeks before the 2008 election: “Of course, Black voters would vote overwhelmingly for any Democratic presidential candidate, not just Obama. But they will very probably vote even more overwhelmingly for Obama.” More pernicious are the caricatures of Black Americans as self-absorbed and unthinking voters. When Colin Powell, George W. Bush’s first secretary of state, announced that he would be endorsing Obama, the conservative media personality Rush Limbaugh criticized him for choosing race over “the nation and its welfare” and several years later suggested Powell would vote for Obama again because “melanin is thicker than water.” The conservative pundit Pat Buchanan, the Georgia state representative Vernon Jones and others have recently resurfaced the old and ugly allegation that Black people are trapped on the Democratic “plantation,” dociles practicing a politics of grievance and gratuity that makes them beholden to the party.

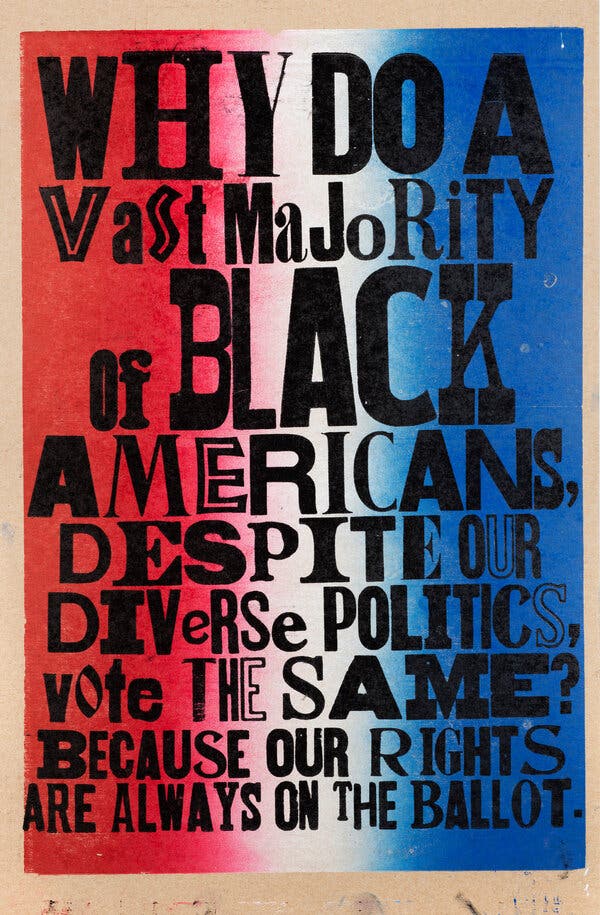

Near-unanimity is undeniably a persistent feature of Black voting behavior. From 1964 to 2008, according to a report by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, an average of 88 percent of Black votes went to the Democratic Party’s presidential nominees, a number that increased to 93 percent in the last three presidential elections. And yet, as my family experience demonstrates, a monolithic Black electorate does not mean uniform Black politics.

Surveys routinely show that Black Americans are scattered across the ideological spectrum despite overwhelmingly voting for Democrats. Gallup data for last year showed that just over two in five Black Americans identify as moderate and that roughly a quarter each identify as liberal or conservative. The University of Texas political scientist Tasha S. Philpot pointed out in a recent podcast interview that “there’s quite a bit of heterogeneity among Black voters that often gets masked when we just look at the outcomes of elections.”

An enduring unity at the ballot box is not confirmation that Black voters hold the same views on every contested issue, but rather that they hold the same view on the one most consequential issue: racial equality. The existence of the Black electoral monolith is evidence of a critical defect not in Black America, but in the American practice of democracy. That defect is the space our two-party system makes for racial intolerance and the appetite our electoral politics has for the exploitation of racial polarization — to which the electoral solidarity of Black voters is an immune response.

It is, however, routinely misdiagnosed. In 2016, campaigning in a Michigan suburb that is around 2 percent Black, Donald Trump prodded Black voters to give him a chance, asking: “What the hell do you have to lose?” and boasted to the nearly all-white audience: “At the end of four years, I guarantee you that I will get over 95 percent of the African-American vote. I promise you.” Earlier this year, the Democratic presidential nominee, Joe Biden, stated matter-of-factly that “unlike the African-American community, with notable exceptions, the Latino community is an incredibly diverse community with incredibly different attitudes about different things.” More crudely, he told the radio host Charlamagne Tha God in May: “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t Black.” (He later distanced himself from both comments.)

These characterizations belie a more ominous reality: Black Americans are canaries in the democratic coal mine — the first to detect when the air is foul, signaling the danger that lies ahead.

To be Black in America has often meant to act in political solidarity with other Black people. Sometimes those politics have been formal and electoral, sometimes they have been of protest and revolt. But they have always, by necessity, been existential and utilitarian.

Black America’s introduction to the democratic republic came via the cold calculus of the Constitution’s Three-Fifths Compromise. A full accounting of the enslaved Black population would have empowered the states championing enslavement by giving such states more representatives in Congress and more votes in the Electoral College; a total exclusion would have expunged their personhood from the sacred text. Democracy to enslaved Black Americans thus initially presented as little more than a negotiation on how their rights and humanity could be bartered away.

When Black men were first enfranchised after the end of the Civil War, they faced a partisan politics reduced to one stark choice: Side with those who would extend more rights of citizenship to Black people or with those who would deny them. Naturally, they largely supported racially progressive Republicans who advocated for Black suffrage and representation. In Virginia, more than 100,000 freed Black men registered to vote for delegates to the convention that would help facilitate the state’s readmission to the Union. On Election Day in October 1867, 88 percent of them voted — often under the threat of job loss — securing a supermajority of convention delegates for Republicans, more than a third of whom were Black. The convention, filled by the electoral solidarity of Black voters and delegates, helped lead to the state’s successful re-entry into the United States, formalize suffrage for freedmen and extend civil rights.

The ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments codified freedmen’s participation in the electoral process at a time when upward of 90 percent of Black Americans lived in the Southern states, constituting actual or near majorities in more than a few. This led to more than 300 Black state and federal legislators in the South holding office in 1872, a level not seen again for more than 100 years. These elected officials were overwhelmingly Republicans swept into office by the unity of Black voters, who assembled to demand equality and liberty that hinged on keeping white segregationists from power.

This was the Black monolith’s forceful debut. In a thriving democracy, one aligned to the nation’s professed values, a competition for these new voters would have ensued. The monolith would have dissipated as individual Black voters sought out their ideological compatriots instead of being compelled to band against segregation and racial violence.

Instead, a campaign of white nationalist terrorism swept across the South, targeting Black Republican legislators and voters. In Georgia, the 1868 State Legislature voted to expel its Black members, all of whom were Republican. They were eventually reseated, but not before white racist vigilantes in the town of Camilla opened fire on Black marchers attending a Republican rally, killing, by some accounts, nearly a dozen and wounding dozens more. That same year in South Carolina, white vigilantes killed a number of Black legislators. One of them, Benjamin F. Randolph, was shot in broad daylight at a train station. No one was ever tried for the crime, let alone convicted of it. In the Colfax Massacre of 1873, dozens of Black Republicans and state militiamen were killed during an attempt to overturn election results in Louisiana.

Federal forces kept some of this racial terror in check, but not all of it. And white Republican leaders occasionally bowed to the violence out of political expedience. In the 1876 presidential election, 19 electoral votes in three Southern states were disputed and accompanied by voter intimidation and widespread voter fraud. In South Carolina, according to the University of Virginia historian Michael F. Holt’s book “By One Vote,” voter turnout was an absurd 101 percent.

The moderate Republican Rutherford B. Hayes lost the popular vote that year, but appeared to have an edge in obtaining the disputed electors, and Republican Party leaders struck a deal with Democrats that would make him president in exchange for a promise that federal troops would not intervene in Southern politics. Once in office, Hayes followed through on his pledge. The Compromise of 1877, as it is now known, effectively traded Black people’s rights for the keys to the White House. It brought Reconstruction to an end, paving the way for the Jim Crow era.

In the first century of American politics, the word “compromise” — Three-Fifths, Missouri, 1850, 1877 — was often a euphemism for prying natural and constitutional rights from Black Americans’ grip. Perhaps betrayals of one group can be labeled compromises by the others, but racial hierarchy and equal rights cannot touch without bruising. These political arrangements underscored the paradox that plagued Black America from the outset: The same federalist government charged with the delivery and defense of constitutional rights was often the means of denying them. On matters of race, the state was at once dangerously unreliable and positively indispensable.

The contours of Black politics were shaped by this quandary. The lack of faith in American democracy’s ability to do what was right undergirded Black conservatism, producing economic philosophies like Booker T. Washington’s bootstrapping self-determination; social efforts toward civic acceptance like the respectability politics of the Black church; and separatist politics like the early iterations of black nationalism. A recognition that achieving racial equality required a strong government fueled Black progressivism, which demanded anti-lynching federal legislation; eradication of the poll tax and other barriers to voting; and expansion of quality public education. Elections might have brought these strains of Black politics together, out of necessity, but did not erase the differences between them.

In the years that followed, the twin phenomena of the Great Migration and the Great Depression carried millions of Black Americans out of the South to new locales in search of physical and economic security, and by 1960, the share of the Black population residing outside of the Southern states had quadrupled to 40 percent. The Howard University political scientist Keneshia Grant has documented in her book, “The Great Migration and the Democratic Party,” how this influx of Black Americans led Northern white leaders and elected officials of both parties to devise campaign strategies and policy positions targeting Black voters.

In the 1930s through the 1950s, that electoral solidarity was hardly a given. Democrats had a progressive economic agenda that appealed to Black voters, but the party was still home to the Southern conservatives ruthlessly enforcing Jim Crow laws. The Republican Party could have mounted a concerted national effort to keep Black voters by refusing to be outflanked on civil rights policies, but its coalition of pro-business interests were less enthusiastic about the regulatory compliance burden associated with civil rights measures on employment, wages, public accommodations and housing.

Instead, Democratic national leadership made the first bold move. A year before the 1948 presidential election, noting the success of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal electoral coalition, a campaign-strategy memo drafted by Clark Clifford and James Rowe, advisers to President Truman, argued that “the Northern Negro voter today holds the balance of power in presidential elections for the simple arithmetical reason that the Negroes not only vote in a bloc but are geographically concentrated in pivotal, large and closely contested electoral states such as New York Illinois, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Michigan.” Truman’s decision to sign executive orders desegregating the military and the federal work force was an electoral broadside constructed, in part, to help win over the support of northern Black voters.

It worked. Truman won 77 percent of Black voters, and with them the Great Migration destination states of Illinois and Ohio by just a combined 40,000 votes — and these states’ electoral votes provided the margin of victory. The famous picture of the re-elected president holding up the erroneous newspaper headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” exists in large part because Dewey, the Republican governor of New York, with a solid record on civil rights, had grown suddenly lukewarm on the issue, making halfhearted appeals to Black voters in the North while increasing entreaties to white conservatives in the South.

Election results will take longer, but not because of ‘unsolicited ballots,’ despite Trump’s claims

Sept. 17, 2020, 9:38 a.m. ET

Lindsey Graham says Comey will testify before a Senate committee the day after the first presidential debate.

Sept. 17, 2020, 9:25 a.m. ET

Obama is publishing the first half of his memoir right after the election.