— By Karl Evers-Hillstrom, with contributions from researchers Doug Weber, Anna Massoglia, Andrew Mayersohn, Grace Haley, Sarah Bryner and Alex Baumgart, Jan. 14, 2020

The proliferation of controversial political advertisements in the past decade isn’t a coincidence. It’s a direct result of the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission ruling, which helped pump billions of dollars into politics from outside sources that are supposed to be untethered from candidates or political parties.

On Jan. 21, 2010, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the longstanding prohibition on independent expenditures by corporations violated the First Amendment. With its decision, the court allowed corporations, including nonprofits, and labor unions to spend unlimited sums to support or oppose political candidates. The majority made the case that political spending from independent actors, even from powerful corporations, was not a corrupting influence on those in office.

The decade that followed was by far the most expensive in the history of U.S. elections. Independent groups spent billions to influence crucial races, supplanting political parties and morphing into extensions of candidate campaigns. Wealthy donors flexed their expanded political power by injecting unprecedented sums into elections. And transparency eroded as “dark money” groups, keeping their sources of funding secret, emerged as political powerhouses.

The explosion of big money and secret spending wasn’t spurred on by Citizens United alone. It was enabled by a number of court decisions that surgically removed several restrictions in campaign finance law, and emboldened by inaction from Congress and gridlock within the Federal Election Commission. Those government bodies remain deeply divided, meaning the mishmash of campaign finance rules spawned by the Supreme Court will likely remain in place in 2020 and beyond.

“In our 35 years of following the money, we’ve never seen a court decision transform the campaign finance system as drastically as Citizens United,” said Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics. “We have a decade of evidence, demonstrated by nearly one billion dark money dollars, that the Supreme Court got it wrong when they said political spending from independent groups would be coupled with necessary disclosure.”

OpenSecrets’ original research indicates:

- Despite fears that elections would be dominated by corporations, the biggest political players are actually wealthy individual donors. The 10 most generous donors and their spouses injected $1.2 billion into federal elections over the last decade. That tiny group of major donors accounted for 7 percent of total election-related giving in 2018, up from less than 1 percent a decade prior.

- The balance of political power shifted from political parties to outside groups that can spend unlimited sums to bolster their preferred candidates. Election-related spending from non-party independent groups ballooned to $4.5 billion over the decade. It totaled just $750 million over the two decades prior.

- Even political candidates found themselves dwarfed by independent groups that in many cases morphed into effective arms of political campaigns and parties. Outside spending surpassed candidate spending in 126 races since the ruling. That happened just 15 times in the five election cycles prior.

- Despite promises from the court that monied interests would be required to reveal their political giving, the ruling gave new powers to dark money organizations. Groups that don’t disclose their donors flooded elections with $963 million in outside spending, compared to a paltry $129 million over the previous decade.

- Major corporations didn’t take full advantage of their new political powers. Corporations accounted for no more than one-tenth of independent groups’ fundraising in each election cycle since the ruling. But secretly funded nonprofits and trade associations that influence elections take money from major companies in amounts that are mostly unknown.

- The ruling didn’t reverse the ban on foreign money in elections, but it provided opportunities for foreign actors to secretly funnel money to elections through nonprofits and shell companies.

Follow the Citizens United Money:

The Courts Trump Congress

In January 2008, Citizens United, a conservative nonprofit corporation, released a 90-minute documentary highly critical of then-presidential contender Hillary Clinton.

Before its release, the group wanted to make the movie available on-demand — and pay to advertise the film — within 30 days of the 2008 primary election, an action that likely would have violated the 2002 Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act.

The law originally stipulated that corporations, including nonprofits, could not use money from their treasuries to fund electioneering communications — messages that mention a political candidate within close proximity to an election. An earlier 2007 Supreme Court ruling, FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, weakened the rule so the ban only applied to communications that rise to the level of expressly advocating the election or defeat of a candidate.

Anticipating penalties over the promotion of its film, Citizens United sued the FEC in December 2007. It argued that the ban on corporate-funded express advocacy, as well as its disclosure and disclaimer requirements, were unconstitutional in the case of this on-demand movie. The U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia sided with the FEC, laying out countless examples in which the film tries to convince viewers to vote against Clinton.

Citizens United appealed, bringing the case to the Supreme Court, which heard its first oral arguments in March 2009. The Supreme Court agreed with the lower court that the film could only be viewed as expressly advocating for Clinton’s defeat. But after multiple oral arguments, the court’s five conservative justices ultimately ruled that laws restricting political speech of corporations were unconstitutional.

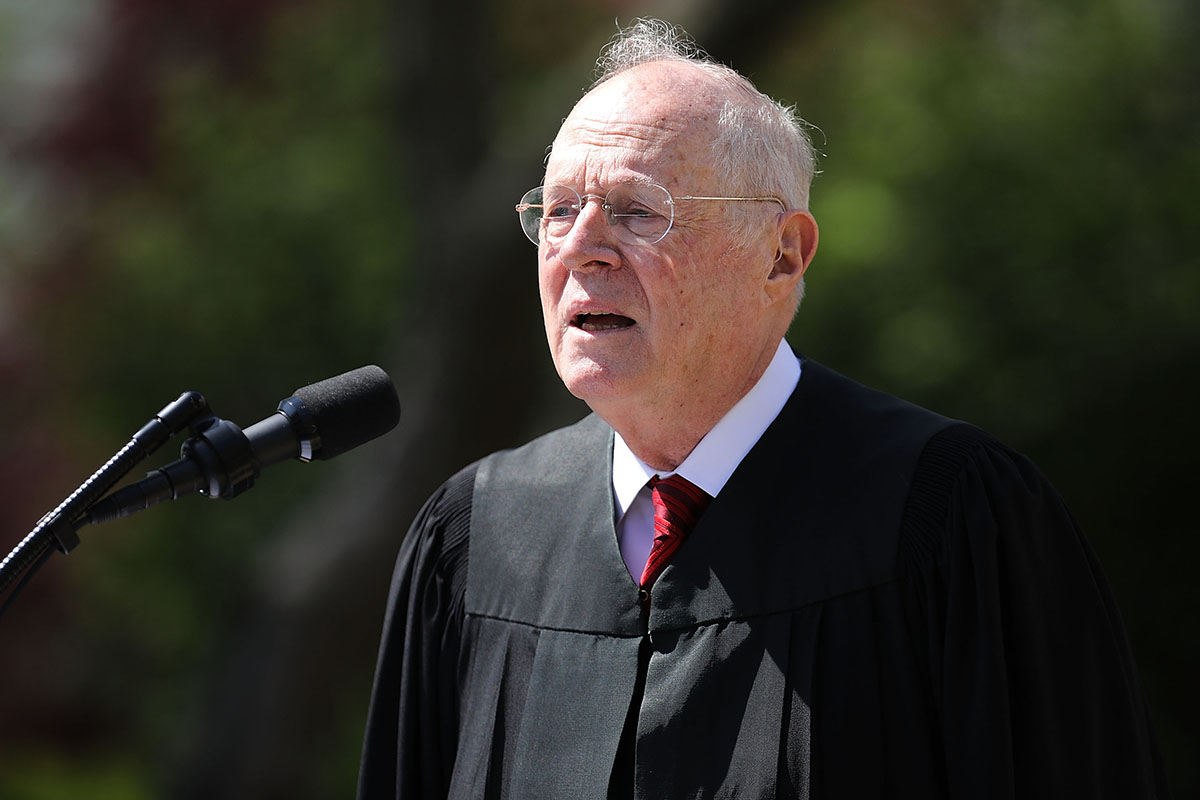

The Citizens United majority relied on the arguments made by Supreme Court justices in 1976’s Buckley v. Valeo in which the court struck down spending limits on independent expenditures. Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy declared that independent spending from corporations or other actors to support or oppose candidates would not give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.

“The appearance of influence or access, furthermore, will not cause the electorate to lose faith in our democracy,” Kennedy wrote. “By definition, an independent expenditure is political speech presented to the electorate that is not coordinated with a candidate.”

The court overruled two major Supreme Court decisions, Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce and McConnell v. FEC, allowing corporations and labor unions to use money from their treasuries to fund electioneering expenses as well as independent expenditures that expressly advocate for or against political candidates.

In Speechnow v. FEC, an appeals court case heard later in 2010, judges applied the Citizens United precedent to PACs. The court ruled that a political committee may accept unlimited contributions from individuals, corporations and unions as long as they do not contribute to candidates or coordinate their activities with candidates or parties. The FEC subsequently allowed the creation of independent expenditure-only committees, now known as super PACs.

Ensuing court rulings further implemented the new precedent. In 2011, a district court ruled in Carey v. FEC that PACs could accept unlimited contributions to one bank account solely for the purpose of independent expenditures and maintain a segregated account that can give money to candidates. The FEC subsequently allowed the creation of hybrid PACs, which can act as a PAC and super PAC.

In 2014, the court struck down another section of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act that limited how much an individual donor could give to candidates and parties every election cycle. The court ruled 5-4 in McCutcheon v. FEC that these limits were unconstitutional, expanding on its own logic in Citizens United that wealthy donors’ increased access with candidates is not corruption.

“Government regulation may not target the general gratitude a candidate may feel toward those who support him or his allies, or the political access such support may afford,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the majority.

The decision enabled the growth of joint fundraising committees that solicit large checks from a handful of wealthy donors and distribute the money among various committees. With these committees, Hillary Clinton raised $577 million for her campaign and Democratic party committees in 2016, and President Donald Trump is raising unprecedented sums for his 2020 reelection effort.

Years prior, the court dealt another blow to the law meant to limit the power of wealthy individuals. In 2008’s Davis v. FEC, the court struck down the Millionaire’s Amendment, which allowed opponents of wealthy self-funding congressional candidates to bypass contribution limits. In recent cycles, self-funding candidates such as Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) and Rep. David Trone (D-Md.) have found success.

Following the court’s string of rulings, campaign contribution limits to candidates, traditional PACs and parties remained intact. The court reaffirmed the ban on unlimited soft money contributions to political parties for the purpose of “party-building” expenses, and the ban on direct corporate contributions to candidates and parties. The court also affirmed the need for campaign contributions to be disclosed to the public, an assurance that was undermined by the majority’s decision that granted new powers to dark money groups.

By surgically removing sections of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act while keeping some parts intact, the court left behind a hodgepodge of rules governing the campaign finance system to this day.

Super PACs Prevail

Money talks. And voters often listen.

The candidate with more money wins more often than not. A larger war chest means more money to hire staffers, produce ads, raise additional funds, travel and establish physical infrastructure.

While most candidates build their campaign coffers over the course of several months, super PACs may solicit seven-figure checks and instantly convert them into an influx of ads, mailers or other communications that can appear nearly indistinguishable from those of the candidates.

In some of the most competitive races, outside groups wage ad wars of their own, battling for spending superiority to influence voters. Since the 2010 midterms, outside spending has surpassed candidate spending in 126 congressional races. In the five cycles prior, that phenomenon occurred just 15 times.

That outside spending is the primary consequence of Citizens United, with non-party groups now dominating presidential elections and the most tightly contested House and Senate contests. Non-party outside groups have spent nearly $4.5 billion influencing elections since the 2010 cycle. Over the previous two decades, they spent a combined $750 million.

This spending contributes to record-breakingly expensive races. When adjusting for inflation, nine of the 10 most expensive non-special election House races ever occurred in the 2018 election cycle. California House races for the 25th and 48th congressional districts were each bombarded with more than $20 million in outside spending. No non-special election House race had reached that mark before.

Eight of the top 10 most expensive Senate races ever occurred after Citizens United with inflation factored in. With $213 million spent — including $97 million in outside spending — the hotly contested 2018 Florida Senate race is the most expensive ever. The 2016 Senate battle between Sen. Pat Toomey (R-Pa.) and Democrat Katie McGinty was blanketed by $127 million in outside spending. The candidates spent $53 million.

Since Citizens United, spending by super PACs and dark money groups, along with non-party independent groups, has accounted for a larger proportion of total election-related spending with each midterm and presidential election.

Candidate and party spending, as a result, has declined as a share of the total. Like super PACs, political party committees may make independent expenditures. But they are hindered by contribution limits and cannot take money from corporations or unions. In 2004, parties spent a record $265 million on outside spending, a figure that hasn’t been surpassed since.

Some super PACs are created for the purpose of bypassing parties and backing candidates who might not normally get party support. Amid the 2010 Tea Party movement in conservative politics, super PACs such as Club for Growth Action and Ending Spending Action Fund emerged as a thorn in the GOP’s side. They spent millions backing their preferred Republicans in primaries, in some cases endorsing primary challenges against GOP-backed lawmakers. That intervention may have cost Republicans Indiana’s Senate seat in 2012 when conservative super PACs organized to take down Sen. Richard Lugar (R-Ind.) in support of losing Republican Richard Mourdock.

Other super PACs assumed the role that parties might normally play in tightly contested elections, only now they could solicit unlimited sums from wealthy donors. Senate Majority PAC and Senate Leadership Fund launched with the blessing of Democrat Harry Reid and Republican Mitch McConnell, respectively. On the House side, party leaders helped launch the liberal House Majority PAC and the conservative Congressional Leadership PAC.

As Kennedy wrote in Citizens United, these groups are supposed to be independent and cannot coordinate their efforts with candidates or parties. It didn’t take long until that theory was irreparably damaged.

Some super PACs effectively operate as extensions of the campaign. They offer donors a way to continue supporting their candidate after they hit maximum candidate contribution limits.

In 2012, both Barack Obama and Mitt Romney attended fundraisers for their own respective super PACs. To stay within the law, the presidential hopefuls avoided explicitly asking their supporters to give to the unlimited-spending groups. Super PACs tied to party leaders spent $389 million boosting candidates in 2012, accounting for nearly two-thirds of all super PAC spending.

Candidates and parties have exposed the countless loopholes in coordination rules over the last decade. One of the more ridiculous episodes of coordination took place in 2014, when the two major parties communicated with outside groups in code in public Twitter posts to concoct their ad buying strategy. The effort abused FEC rules that allow outside groups to use information from candidates or parties that is distributed on a public forum.

Jeb Bush raised money for Right to Rise USA, a super PAC backing his 2016 presidential bid, before he officially announced his candidacy, successfully avoiding unlawful coordination. Effectively an arm of the campaign, the group spent $84 million on pro-Bush ads, some of which looked eerily similar to the Bush campaign’s ads.

Bush wasn’t alone. Most of the top Republicans in that race had their own super PAC. The result was an unprecedented $531 million in outside spending by single-candidate super PACs in the 2016 cycle.

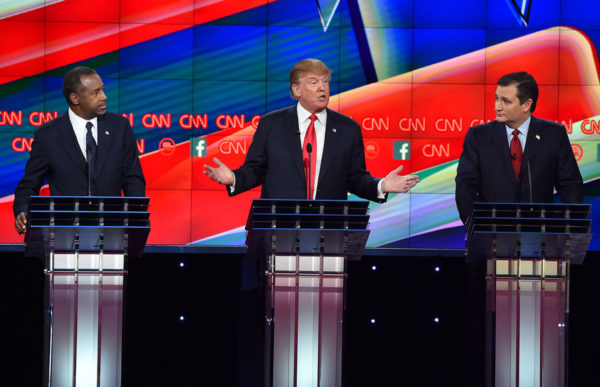

Trump was the exception. The real estate mogul didn’t have his own super PAC in the primary. He used that fact to his potential advantage, accusing his opponents of being “in total cahoots” with their closely tied outside groups and acting as “puppets” for megadonors such as the Koch brothers and Sheldon Adelson. He railed against modern campaign finance rules, pledging to “fix that system” and calling super PACs “corrupt.”

Then-candidate Donald Trump attacked his Republican opponents for having closely tied super PACs. (Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images)

That campaign promise never materialized. After winning the Republican nomination, Trump effectively dropped his opposition to super PACs. Numerous groups, including an Adelson-backed super PAC, emerged late to back Trump in his upset victory. Trump claimed that Adelson would back his Republican opponents in 2015 to influence them. But it was Trump who found himself pushing for Adelson’s interests as president.

Trump has embraced the super PAC during his time in the White House. In May 2019, Trump endorsed a super PAC, America First Action, as the campaign’s only “approved” outside group. In November, Trump headlined a big-ticket fundraiser for the group, which is supposed to be independent of the Trump campaign.

The Trump era highlights how some super PACs can be closely connected to a campaign while others are truly independent. A number of outside groups are raising money in Trump’s name despite being disavowed by the Trump campaign, which is powerless to stop them.

But America First Action is widely viewed as an arm of the Trump campaign, even by those attempting to curry favor with the president. For example, Steel tube manufacturer Zekelman Industries gave $1.75 million to the group in 2018 as it aired ads attacking various Democrats. The large gift was approved by the company’s Canadian CEO Barry Zekelman, who was personally lobbying the administration over its steel policy at the time.

Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, associates of Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani, made a $325,000 contribution to America First Action through a shell company. They were later indicted for allegedly making straw contributions on behalf of a Ukrainian government official who sought to influence the Trump administration. Foreign nationals are barred from making political contributions.

Trump’s flip-flop on super PACs isn’t unprecedented. Obama routinely blasted super PACs and pledged in 2011 that he would not fundraise for them. The campaign reversed course just seven months later, giving former White House aides the green light to launch a super PAC, Priorities USA Action. Obama’s campaign manager Jim Messina wrote that the campaign would not “unilaterally disarm” and let Republicans dominate the super PAC landscape.

The 2020 election initially looked like it would be different. Each of the top Democratic contenders launched their campaigns with the promise that they would not embrace super PACs. They coupled that pledge with the goal of supporting a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizens United.

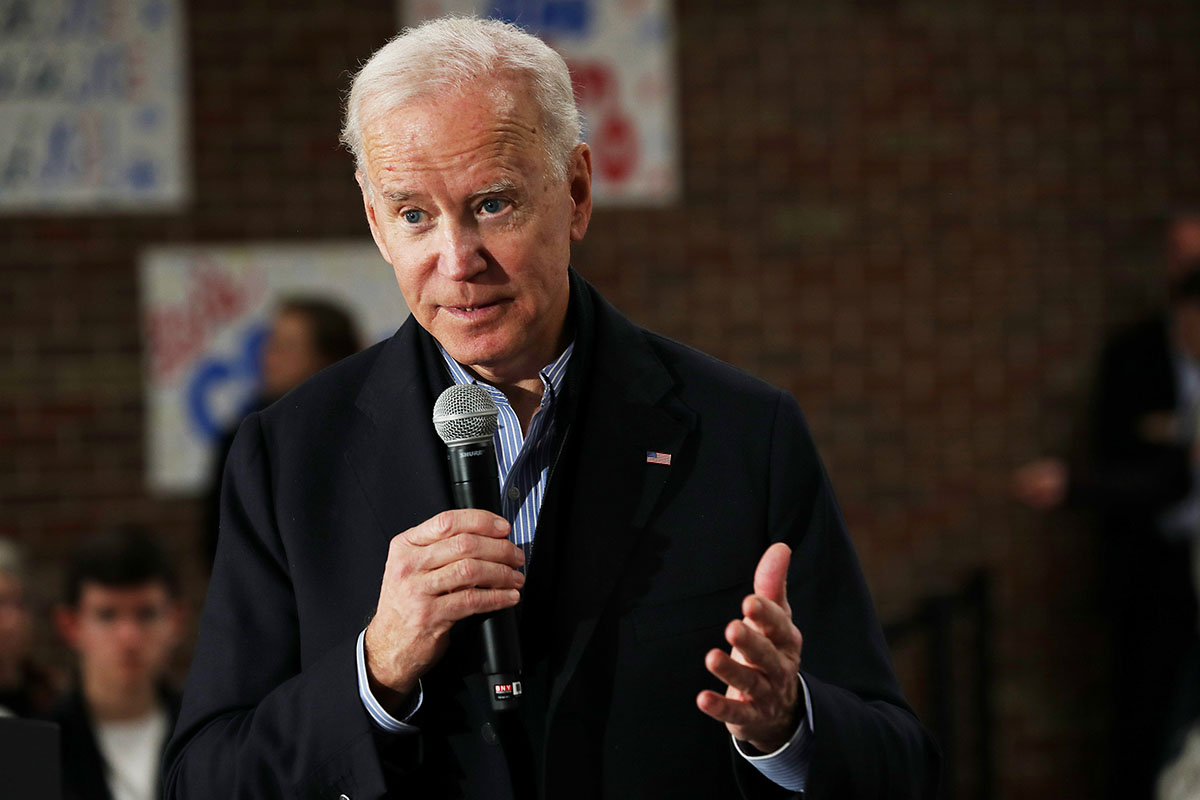

Former Vice President Joe Biden stuck by his pledge only until the campaign experienced the first sign of trouble. In October 2019, the Biden campaign, low on cash and having already taken a large chunk of its money from donors who already donated the maximum amount, dropped its opposition to a super PAC. In less than a week, longtime Biden aides launched a super PAC, Unite the Country. Within a month, the group spent a whopping $2.3 million on ads supporting Biden.

Presidential candidate Joe Biden was boosted by millions in super PAC support through the end of 2019. (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Whether a candidate supports a super PAC appears to impact the group’s success with wealthy donors. A super PAC supporting Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), Dream United, shut down shortly after Booker denounced outside spending on his behalf. The group’s founder said that Booker’s donors were “strictly adhering” to the presidential hopeful’s super PAC policy.

Outside groups are finding all kinds of encouragement from critical Senate candidates ahead of 2020. As Sen. Martha McSally (R-Ariz.) faced attacks from Democratic dark money groups and super PACs, she openly pleaded for outside support on the airwaves ahead of her 2020 election. She said her campaign couldn’t afford to air multi-million dollar television ad blitzes.

“We need close air support to show up,” McSally told Republicans in December. “There’s outside groups. We can’t talk to them. We can’t invite them, but we pray for them every day.”

Campaign aides for Democrat Amy McGrath, who hopes to unseat Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) in 2020, said they “strongly encourage” donors to give to a new super PAC called Fire Mitch Save America.

“I think the signal is for people who are interested in contributing beyond the legal limits, they should have confidence to contribute to the Super PAC,” McGrath’s campaign manager told the Lexington Herald Leader.

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) invited outside support by uploading six minutes of soundless, high-resolution campaign footage to YouTube. By publicly publishing b-roll, candidates legally provide super PACs with footage for their ads. A group backing her campaign, 1820 PAC, used the footage in pro-Collins ads. Funded mostly by New York investor Stephen Schwarzman, the group spent $701,000 supporting Collins through mid-January.

By the letter of the law, campaign coordination with outside groups is illegal. But the FEC, tasked with enforcing campaign finance law, has not once penalized a political candidate or group for unlawful coordination since Citizens United.

The only instance of campaign coordination being punished took place in 2015. A Virginia Republican operative was convicted in federal court of illegally coordinating super PAC spending with a congressional campaign he was running. It was the Justice Department, not the FEC, that brought the case. Justice Department officials noted at the time that illegal coordination is “difficult to detect” and urged “party or campaign insiders to come forward.”

The FEC has become synonymous with paralysis in recent years. The agency has up to six members — with several seats often left vacant due to partisan impasse in Congress — and no more than three commissioners may be members of the same party. Official actions require four votes, leading to “deadlocks” where Republican and Democratic commissioners can’t agree on the best course of action. The divide is ideological in nature. Republicans argue that strict application of campaign finance laws chills free speech, using that logic to consistently throw out complaints levied against members of both parties. Democrats say Republicans fail to investigate credible evidence of campaign finance violations by members of both parties.

As of January 2020, the FEC doesn’t have enough members to conduct meetings or pursue investigations. (Sarah Silbiger/CQ Roll Call)

In one high-profile example, Republican commissioners dismissed a complaint alleging that Hillary Clinton coordinated with a closely tied hybrid PAC, Correct the Record, on campaign messaging and tactics, going against recommendations from the agency’s top lawyer. The commission’s lone Democrat and independent voted to move the investigation forward.

Republicans in Congress also cite free speech concerns when fighting Democratic bills meant to tighten campaign finance rules. The divide between the parties is stark, despite the fact that both use super PACs and dark money groups to win elections.

Republicans have received more outside support than Democrats since Citizens United. Over the last decade, conservative non-party outside groups spent $2.6 billion on outside spending compared to liberal groups’ $1.7 billion. The numbers are skewed by the 2012 election where Democrats were outspent by independent groups 2-to-1 but still held the presidency and the Senate. The 2018 midterms, marked by massive Democratic gains in the House, was the first election cycle since Citizens United that Democratic outside groups outspent their Republican counterparts.

Some Democrats feared that corporations would dominate electoral politics thanks to the Citizens United decision. For the most part, that didn’t happen.

Corporations continue to curry influence with lawmakers by donating through traditional PACs, which are funded by wealthy executives and are subject to contribution limits. They also spend heavily on lobbying and public relations campaigns, not all of which is disclosed to the public, to sway lawmakers over specific issues.

But most corporations don’t make independent expenditures or give to super PACs at the federal level. Major companies have stayed away due to the risk of backlash from consumers and resentment from lawmakers they want to sway. OpenSecrets found that just 36 companies on the S&P 500 contributed $25,000 or more to super PACs since 2012. The largest donors on that list are Republican-backing oil & gas companies such as Chevron and NextEra Energy.

Corporations gave $301 million to super PACs and hybrid PACs from the 2012 to 2018 cycles, 87 percent of which went to conservative groups. These contributions made up 10 percent of funding to these groups in the 2012 cycle, a high water mark. That figure dipped to just 5 percent in 2018.

Some U.S. subsidiaries of foreign companies have given million-dollar gifts to super PACs. The pro-Jeb Bush Right to Rise USA took $1.3 million from a Chinese-owned company, resulting in a rare fine from the FEC. In this case, the FEC had evidence that Chinese nationals in control of the company facilitated the contribution, thanks to an earlier report from The Intercept. Commissioners have not been able to agree on how subsidiaries of foreign companies should be treated under law.

The most popular destination for corporate funds are the Republican presidential super PACs such as Bush’s Right to Rise ($26 million) and Romney’s Restore Our Future ($28 million) and Republican Party-connected groups like American Crossroads ($39 million) and Senate Leadership Fund ($34 million).

The amount of election-related giving from corporations is almost certainly higher than disclosed. That’s because corporations prefer to fund trade associations and politically active 501(c)(4) groups that don’t disclose their donors, as discussed in this report’s dark money section.

Corporations are often compared to labor unions in the scope of Citizens United. Corporations mostly give to Republican efforts, while labor unions are mostly united behind Democrats. Both were given increased political power following the ruling.

Labor unions were among the top outside spenders for Democrats in the years before Citizens United. They engaged in express advocacy to support or oppose candidates using traditional PACs and used treasury funds to distribute policy messages to union members in what the FEC calls communication costs.

Unions took advantage of Citizens United by creating their own network of super PACs and giving heavily to Democratic-allied outside groups.

Labor’s efforts swelled in 2016 as they organized to oppose Trump. That cycle, unions gave $91 million to unaffiliated outside groups and spent $92 million through their own PACs, super PACs and union treasuries. United We Can, a super PAC backed by the Service Employees International Union, spent $12 million unsuccessfully supporting Clinton over Trump.

Unions are effectively funded by small donors, as they receive their funding from dues paid by their vast network of donors. Unions are more transparent than corporations as they must disclose their contributions to political groups, including those that don’t disclose their donors. Still, that information isn’t made public until after voters go to the polls.

While corporations and unions gained potential political power as a result of Citizens United, it’s individual donors who are fueling the explosion of money in recent elections.

The Modern Megadonor

Since Citizens United, the top 10 donors and their spouses gave a combined $1.1 billion to outside groups such as super PACs. The top 100 donors and their spouses to these unlimited spending groups accounted for over $2 billion. In an era where outside groups fill crucial roles, between functioning as arms of political parties or as extensions of political campaigns, wealthy donors are indispensable.

Most people will never give to a super PAC. And even among super PAC donors, a tiny minority accounts for most of the money. The top 1 percent of super PAC donors accounted for 96 percent of funding to these groups in 2018. Together, those 1,562 donors gave $818 million. The rest of the super PAC donors gave just $34 million.

That’s in contrast to the record numbers of Americans giving money to political candidates in the most recent presidential and midterm election cycles. High-profile candidates for Congress and the presidency rely on armies of small donors to fund their campaigns. But one check from a wealthy donor, such as 2020 Democratic presidential contender Michael Bloomberg‘s record $20 million gift to the liberal Senate Majority PAC, could effectively neutralize the efforts of thousands, even millions, of small donors.

In the two decades before Citizens United, Bloomberg gave less than $1 million to federal candidates and groups. He’s given $163 million since the ruling, with his efforts helping gun control groups outspend gun rights groups for the first time in 2018.

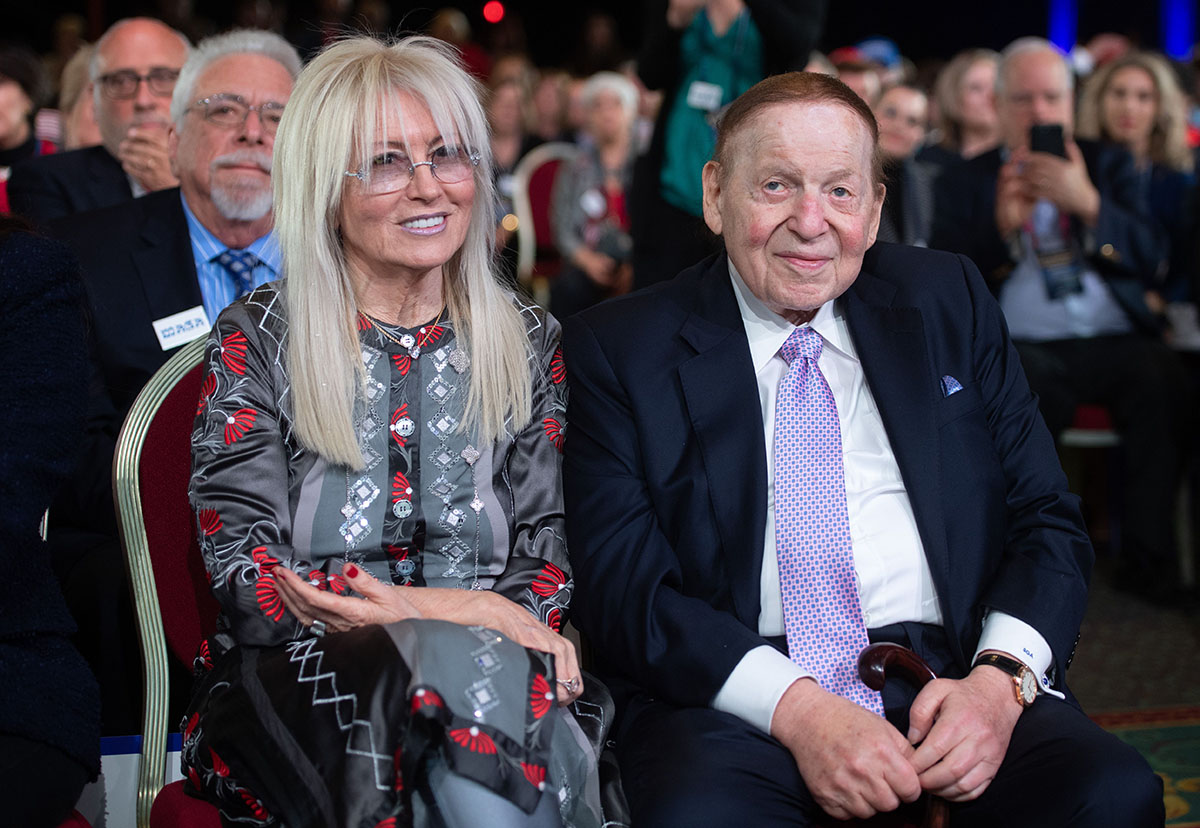

The former New York City mayor may have been influential in 2018, but he is dwarfed over the last decade by casino mogul Sheldon Adelson and his wife Miriam, a physician. The two gave $306 million entirely to Republican candidates and causes, including a single-cycle record $124 million in 2018. The Congressional Leadership Fund, a super PAC closely tied with Republican House leaders, received $55 million from the Las Vegas billionaires.

Billionaire donors aren’t new. But they didn’t have as many ways to directly influence elections before Citizens United. Much of that money went to 527 organizations, political groups that ran politically focused ads but could not expressly advocate for the election or defeat of federal candidates. Wealthy individuals had the option to self-fund independent expenditures and sponsor ads themselves, but rarely did so. During the 2008 presidential election, the most expensive of its kind at the time, the 10 largest donors accounted for $37 million in total giving.

Ten years later, the top 10 largest donors and their spouses gave $447 million, accounting for 7 percent of all election-related giving in the 2018 cycle. Ninety-seven percent of that cash went to outside spending groups such as super PACs.

Super PAC giving is dominated by men, who on average, hold significantly more wealth than women. Economic disparities, including the racialized and gendered wealth gap, mean that women and people of color have fewer resources to spend politically. Men accounted for at least 80 percent of individual contributions to outside groups in every completed election cycle since the Citizens United decision. Since the 2010 cycle, men have given nearly $2.5 billion to outside groups, compared to less than $584 million from women.

That discrepancy stays consistent in recent cycles as women give more to candidates, parties and traditional PACs — known as “hard money” — now then they did in previous decades. In 1990, women accounted for just 22 percent of itemized hard money contributions. By 2000, that number crept up to 28 percent, and in both 2016 and 2018 women accounted for one-third of itemized contributions.

Super PACs rely on big donations, and women on average to give in much smaller amounts than men. More than 1 million women have already donated to 2020 presidential candidates, nearly keeping pace with the number of men. But for every itemized dollar going to a presidential candidate, about 57 cents comes from a man and 43 cents from a woman.

Republican and conservative groups ($273 million) received more money from women than Democratic and liberal groups ($171 million). But Miriam Adelson, who has given $144 million since 2010, single handedly accounts for over half of that sum.

Miriam and Sheldon Adelson have given more than $306 million to Republican candidates and causes since 2010. (Saul Loeb/AFP)

Super PAC contributors are partisan, with almost all of the megadonors giving their money to outside groups supporting one party or the other. Of the 50 most generous donors to outside groups since Citizens United, only billionaire Boston investor Seth Klarman gave significant funds to both conservative and liberal outside groups. That’s because Klarman started the decade backing Republican-allied groups but shifted his contributions to Democratic super PACs in 2018 over his opposition to Trump.

Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos, estimated to be the richest man in the world, is one of the few top donors who gave to a group that supports both Democrats and Republicans. In 2018, he gave $10 million to With Honor Fund, a super PAC that backs military veterans of both parties.

Bezos was one of 30 “guardian angels” — a single donor accounting for 40 percent or more of a major outside group’s funding — OpenSecrets tracked in the 2018 cycle. Illinois shipping giant Richard Uihlein sponsored seven of these groups in 2018 and already makes up nearly half of the funding for conservative super PAC Club for Growth Action ahead of 2020.

Tom Steyer, who like Bloomberg is self-funding his presidential bid in 2020, accounts for the bulk of funding for his liberal groups NextGen Climate Action and Need to Impeach. Steyer gave $260 million to outside groups over the last decade, topped only by the Adelsons. In backing his own environmental group, Steyer single handedly brought environmental interest giving close to the long-dominant oil & gas industry.

Billionaire investor Tom Steyer is self-funding his 2020 presidential campaign after giving more than $260 million to liberal causes. (Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images)

Just as the growth in giving to outside groups didn’t benefit men and women equally, only a few select industries have taken advantage of Citizens United.

The biggest winner is the securities and investment industry, which overtook retirees as the top industry in each of the last four election cycles. While retirees give almost all of their money to candidates and parties, well-paid Wall Street executives, hedge fund managers and investors give big dollars to outside groups. The affluent industry accounts for one-fifth of all money to outside groups since the creation of super PACs.

Writing the dissent in Citizens United, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens predicted that the ruling “dramatically enhances the role of corporations and unions—and the narrow interests they represent—vis-à-vis the role of political parties—and the broad coalitions they represent—in determining who will hold public office.”

It turned out those narrow interests aren’t just corporations or unions. The biggest donors are individuals behind the most powerful and well-funded industries in the country. One person may use their wealth to push their specific interests to the forefront of electoral politics simply by giving millions of dollars.

Most industries, particularly those that aren’t home to many wealthy individuals, barely give any money to outside groups. The education industry gave just 5 percent of its money to outside groups despite ranking as a top-10 industry. Even prolific industries like lawyers/law firms or health professionals give less than one-tenth of their campaign cash to outside groups.

Just as most corporations stay away from super PACs, lobbyists generally don’t give money to these outside groups that air partisan attacks on lawmakers they want to sway. The influential industry has given $188 million, roughly split between Republicans and Democrats, since the creation of super PACs. But just 3 percent of their money went to outside groups.

Hard money has also been impacted by the Citizens United precedent. In 2014’s McCutcheon v. FEC, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority struck down limits on how much an individual donor can give to candidates, parties and PACs in an election cycle. Those limits never applied to outside groups such as super PACs.

A district court upheld the limits in 2012, arguing that donors could circumvent contribution limits to candidates, parties and PACs by giving to a number of groups that then give to the donor’s preferred candidate. Something similar occurred in 2016, when Hillary Clinton’s joint fundraising committee appeared to circumvent contribution limits by routing money to state parties that then funneled it back to the Democratic National Committee.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton routed money from state parties to her presidential campaign thanks to the removal of giving limits. (Samuel Corum/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Chief Justice Roberts rejected the idea that donors would abuse the lack of overall giving limits. He argued that donors seeking influence would rather see their money spent independently to support their preferred candidate “rather than see it diluted to a small fraction so that it can be contributed directly by someone else.” In doing so, he appeared to undermine his 2010 conclusion that independent spending cannot give rise to quid pro quo corruption.

The ruling allowed megadonors to give much more to candidates and parties. In the 2012 cycle, donors could give $46,200 to federal candidates and $70,800 to PACs and parties. During the 2016 election, the first full cycle after limits were removed, donors began giving millions in hard money. The Adelsons gave $4.6 million, and Chicago billionaires James and Mary Pritzker gave nearly $3.4 million.

Donors gave a midterm record $526 million to 814 joint fundraising committees in the 2018 cycle. A committee affiliated with former House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) brought in nearly $65 million and funneled millions to committees that could give to Republican House candidates. Another House GOP group, Protect the House, brought in $26 million and distributed the money among 46 committees.

House Republicans’ joint fundraising committee to take back the House in 2020 has already raised $26 million. Trump is drawing unprecedented fundraising from these committees ahead of 2020, raising hundreds of millions for his campaign and the Republican National Committee between his small-dollar committee and Trump Victory, which facilitates six-figure checks from wealthy donors. Without a presidential nominee for the party, Democrats are falling far behind in joint fundraising efforts, leading to serious money troubles for the Democratic National Committee.

Dark Money Infiltrates Elections

Citizens United suddenly and dramatically increased the power of dark money groups — namely nonprofit groups that are not required to disclose their donors — to directly influence federal elections. These secretive groups spent $963 million on elections over the last decade without informing voters who paid for their ads.

Three years before Citizens United, the Supreme Court’s conservatives ruled in FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. that nonprofit groups could use corporate funds to run ads just before an election as long as they didn’t expressly advocate for or against a candidate’s election.

If not for Citizens United, the 2007 decision might have been held up as the reason for an explosion of dark money. Nonprofit groups were already starting to take advantage of Wisconsin Right to Life before the Supreme Court upended the campaign finance system three years later. During the 2008 presidential election cycle, nondisclosing entities spent $102 million on outside spending meant to influence crucial races. In the four election cycles prior, they spent a combined $26 million.

The Citizens United ruling took things further by allowing nonprofits to spend corporate treasury funds on ads that expressly advocate for or against a candidate’s election. These anonymously funded groups swiftly put their new powers to use. Dark money groups launched $139 million in FEC-reported outside spending during the 2010 midterms, then shelled out a record $313 million during the 2012 election cycle.

Conservative groups, such as Karl Rove’s Crossroads GPS and the Koch brothers-backed Americans for Prosperity, dominated the dark money game, accounting for 86 percent of outside spending from these groups.

All but one of the Supreme Court justices, associate justice Clarence Thomas, rejected Citizens United’s request to strike down campaign finance rules that require disclosure of donors. But the majority did not acknowledge in their opinion that corporations, including nonprofit corporations, are inherently opaque in their structure.

Regulated by the Internal Revenue Service, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit may spend unlimited sums on political activities without ever disclosing donors so long as its primary purpose is “social welfare.” The IRS has not clearly defined what a primary purpose is or issued rules on how to calculate it, but the generally accepted test is that less than half of a 501(c)(4) nonprofit’s activities may be political. In order to stay under the 50 percent threshold, some dark money groups funnel anonymous cash to each other in complex networks.

The IRS has not attempted to clamp down on politically active nonprofits in recent years. (Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP via Getty Images)

Kennedy wrote in the majority opinion that disclosed information about independent spenders “enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.” He said advances in technology would make disclosure faster and more effective.

“With the advent of the Internet, prompt disclosure of expenditures can provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters,” Kennedy wrote in the majority opinion. “Shareholders can determine whether their corporation’s political speech advances the corporation’s interest in making profits, and citizens can see whether elected officials are ‘in the pocket’ of so-called moneyed interests.”

Before the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act was slowly eroded, it appeared to usher in a short-lived era of transparency. Roughly 97 percent of outside spending in the 2004 presidential election cycle came from groups that disclosed their donors, followed by 87 percent in 2006.

That number dropped to 65 percent in 2008 following FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc., then further to 48 percent in 2010 and 40 percent in 2012 before recovering in recent years.

The decade after Citizens United ushered in the rise of “grey money” groups that disclose only some of their donors. Partially-disclosing political groups were practically nonexistent before 2010 and have increased most cycles since. Nonprofits and secretive shell companies began to funnel money to super PACs. Although super PACs are required to disclose their donors, that information doesn’t go beyond the name and address of a nonprofit or company, in many cases leaving the true source of money hidden.

Limited liability companies gave $82 million to outside groups such as super PACs between the 2012 and 2018 cycles, including a record $35 million in 2016. Some of those contributions were made by shell companies created to mask the original source of money.

Dark money groups funneled $176 million to super PACs and hybrid PACs during the 2018 midterms. While dark money spending fell, the percentage of grey money in outside spending hit a record high in 2018, totaling more than $391 million and accounting for more than a third of spending by all non-party outside groups.

Grey and dark money spending by groups that don’t fully disclose donors has exceeded $2 billion since Citizens United. That only includes spending that is reported to the FEC, such as independent expenditures and electioneering communications. It doesn’t include millions of dollars spent on issue ads meant to boost or weaken candidates before election season draws near.

Following the bombardment of ads from nondisclosing groups, it became apparent, even to Kennedy, that the modern campaign finance system was not providing transparency to voters. In 2015, Kennedy lambasted the FEC and other agencies for not doing more to require politically active groups to disclose their donors. The author of the Citizens United ruling said the modern-age disclosure system he championed is “not working the way it should.”

Former Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy acknowledged his decision was not followed by proper disclosure. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The FEC has proved powerless in the battle against dark money. The bitterly divided commission voted several times on new regulations to compel the disclosure of donors to nonprofit groups making independent expenditures but Republican commissioners rejected them. The commission has consistently dismissed complaints against political nonprofits, including those that appear to be organized specifically for the purpose of making independent expenditures. That includes a complaint against Carolina Rising, a pop-up group that spent nearly all of its $4.9 million budget to help elect Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.) in 2014.

In August 2018, a U.S. District Court judge found that the FEC improperly allowed nonprofits to skirt disclosure requirements. In response, the FEC released guidance on the subject, stating that any group that spends at least $250 on independent expenditures must report every donor who gave at least $200 for “political purposes” in the calendar year.

Following the court decision and guidance, 17 groups were informed they would have to disclose their donors. Just four groups provided a list of donors for the 2018 election cycle — and those lists only included names of other dark money groups or affiliated nonprofits. Without a clear definition of what constitutes a contribution for a political purpose, many groups claimed they did not receive contributions specifically meant to be used for political purposes. Even the top dark money spender of the election cycle, the Senate Democratic leadership-linked Majority Forward, told the FEC it did not receive any contributions for political purposes and refused to disclose its donors despite spending more than $45 million to boost Democrats.

Congress has also failed to pass dark money legislation. After Citizens United, Democrats attempted to compel transparency with the DISCLOSE Act, which made its so any group, including corporations, political nonprofits, trade associations and unions that spent $10,000 or more on FEC-reported spending must disclose the source of all contributions of $10,000 or more that election cycle. Republicans aggressively filibustered the bill, successfully preventing it from garnering 60 votes in the Senate. They argued it unfairly benefitted unions — which receive most of their funding from relatively small member dues — over corporations.

As discussed earlier in the report, corporate contributions have mostly benefited Republicans while unions mostly back Democrats. Most major corporations avoid giving to super PACs, where their disclosed contributions to these hyper-partisan groups could spark outrage among potential customers or clients. But pieces of evidence show that corporations funnel money into electoral politics through dark money groups instead to avoid scrutiny.

Americans for Job Security, a trade association that spent millions opposing President Barack Obama and other Democrats, was forced to reveal its donors last year following a lawsuit by Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. The legal win, the first of its kind in the post-Citizens United era, exposed numerous contributions from major corporations.

Well-known companies such as Quicken Loans and Bass Pro Shops directly gave to the group, according to the disclosure. Companies that received massive sums from government contracts, such as Hensel Phelps Construction and B/E Aerospace, also funneled money to Americans for Job Security. Government contractors are barred from making contributions to federal candidates and PACs, and the FEC has fined contractors for funding super PACs. Companies can avoid this ban by funding politically active nonprofits and trade associations.

In most cases, the only way to know how much money a major company gives to dark money groups is if it voluntarily discloses its political contributions. Shareholders of public companies are increasingly pushing for this transparency. According to the Center for Political Accountability, 49 percent of companies on the S&P 500 don’t disclose their contributions to 527 groups — information that is already made public by the IRS anyway. Far more companies, 64 percent, do not disclose their contributions to 501(c)(4)s, leaving hundreds of powerful companies unaccounted for.

Hundreds of powerful S&P 500 companies do not disclose their contributions to dark money nonprofits. (Johannes Eisele/AFP via Getty Images)

Some of the biggest dark money players over the last decade are funded by major corporations. In some cases, they take cash from foreign companies, raising the question of whether the influx of dark money was at least partially backed by foreign money. Foreign nationals and foreign-owned corporations are barred from spending in U.S. elections.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, for example, receives member dues from corporations it represents, including foreign-based companies. The conservative group says it does not use foreign money to fund election-related messages. The Chamber has spent $143 million on elections since the 2010 cycle, making it the top dark money spender post-Citizens United.

The National Rifle Association‘s 501(c)(4) arm, which has spent $59 million boosting Republicans since Citizens United, has taken big checks from affiliates of foreign-owned gun manufacturers such as Germany’s SIG Sauer and Italy’s Beretta. The American Chemistry Council, another politically active trade association, has several foreign companies among its members.

Even contributions from legally formed companies may not be what they seem. CEO Andy Khawaja was indicted in December 2019 for allegedly routing $3.5 million to political committees in the form of personal donations and contributions from his payment processing company, Allied Wallet, as a straw donor for United Arab Emirates adviser George Nader.

Shell companies also provide opportunities for foreign intervention. Jho Low, a Malaysian financier accused of stealing billions from his home country, allegedly funneled more than $1 million to a pro-Obama super PAC through a shell company in 2012. Low was indicted in 2019 on an array of charges including campaign finance violations.

It is impossible to say how much foreign money goes to politically active nonprofits and trade associations, as these groups do not disclose information about their funding sources. Reported contributions from shell companies with little paper trail or public image leave voters with useless information.

The jumbled mismatch of campaign finance laws in the post-Citizens United era allows for unlimited sums of money to flow into U.S. elections, some disclosed and some not. The FEC and Congress have not closed the loopholes created by the ruling that enable dark money to flood the airwaves. Amid deep partisan divisions in Congress and a paralyzed FEC that can’t even conduct meetings without action from the president, it appears highly unlikely that will change before the 2020 election or beyond.

OpenSecrets.org is the nation’s premier website tracking the influence of money on U.S. politics, and how that money affects policy and citizens’ lives.