Joe Biden still has a long way to go to earn Nicole Small’s respect.

Small, a human resources worker in Detroit and vice chair of the commission that considers revisions to the city’s charter, said she was furious after the presumptive Democratic nominee’s “then you ain’t black” gaffe last month — and that he hasn’t done “nearly enough yet” in responding to the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis police custody.

And yet, Small, who is black, says Biden has earned her vote.

“I will chew on nails dipped in acid before I vote for Donald Trump or don’t vote at all, or let my friends and colleagues vote for Trump or not vote at all,” she said.

In Michigan, a key 2020 battleground, quickly changing circumstances brought on by the coronavirus have kept the still-nascent general election race in flux — effects likely to be felt through November. Frustration over President Donald Trump’s response to a pandemic that has killed more than 100,000 Americans and caused the unemployment rate to spike to record highs threatens to alter the political tides in other swings states, including Florida and Pennsylvania.

But interviews with voters like Small — as well as with former lawmakers, political strategists, activists, journalists and political experts in Michigan — indicate that what may impact the election here more than anything is how the lives of black Americans in particular have been upended by what Massachusetts Rep. Ayanna Pressley called a “pandemic within a pandemic”: black people sickening and dying of COVID-19 at disproportionate rates while suffering from the epidemic of police brutality currently being protested in the streets.

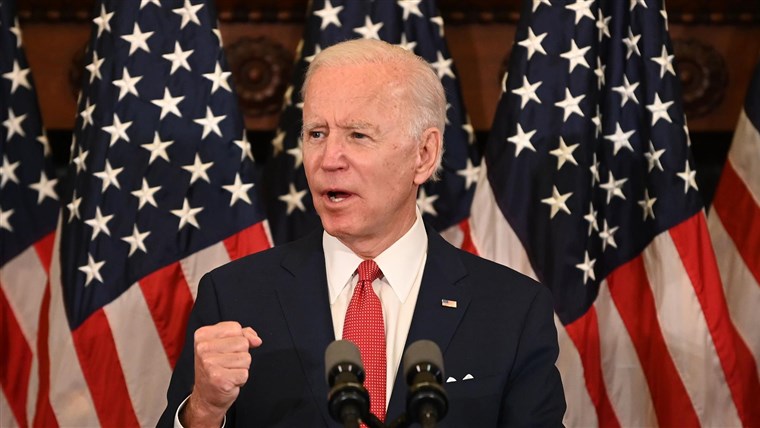

Biden, who has enjoyed strong levels of support from African American voters throughout the campaign, stands to benefit politically, they said. But given what happened in 2016 — when polls showed that Michigan was also Hillary Clinton’s to lose, and then she lost it — black voters and Democratic political strategistswarned that Biden must do more to appeal to and turn out African American voters in order to compete with the white working class contingent Trump so adeptly mobilized in 2016, and who could turn out en masse for him again.

“The African American community is motivated to come out to have Trump removed. Unlike when Hillary was running, no one truly knew how bad Trump could be,” said LaMar Lemmons, a former Democratic member of the Michigan state House. “The pandemic was really the last straw for many people. Of course now we’re talking about the protests, but Trump’s nonresponse to the pandemic has really alienated the African American community.”

“But if he [Biden] really wants to be sure he’s reaching voters, and reaching black voters, he needs to come here and campaign,” added Lemmons, who remains a political activist in Detroit.

Michigan has been particularly hard-hit by the coronavirus outbreak, from both health and economic standpoints. As of Saturday night, the state had the ninth-most confirmed cases of COVID-19 and the sixth-most deaths from the virus in the U.S.

More than 1.5 million Michiganders have lost their jobs since March 14, representing a whopping 31.2 percent of the workforce. About 40 percent of all COVID-19 deaths in Michigan have been African Americans, even though only about 14 percent of Michiganders identified as African American or black in the latest Census. Trump, whose response to the pandemic has been criticized as slow and ineffective, attacked the state’s Democratic leadership and encouraged demonstrations against the strict stay-at-home orders (including armed protests inside the state Capitol) put in place to help slow the spread of the virus.

“We have been disproportionately affected. Most everyone I know knows people who have died from COVID,” Lemmons said. “We know what we have to lose now,” he added, nodding to an infamous Trump campaign line. “Our lives.”

Small, who said 11 people across her social circle have died from COVID-19, said Trump’s response to the coronavirus and protests should be “proof to anyone” that he should lose his job in November.

But while Small said she is absolutely committed to voting for Biden, she explained she will do so dispassionately, unless he manages to “up his game” when it comes reaching out directly to black voters with a convincing message and a more forceful response to the protests.

To win Michigan, politics watchers said, Biden can’t rely solely on black voters like Small who plan to turn out no matter what — he must inspire African American Michiganders who might not otherwise go to the polls.

Trump won the state in 2016 by less than 11,000 votes — the first time the state went red in a general election since 1988.

While his campaign was credited in Michigan (and elsewhere) with a strong effort of targeting white working class voters and a Republican turnout operation that motivated voters who had previously been disengaged in politics, experts have heavily attributed his win to a deeply flawed campaign strategy by Clinton that failed to turn out black voters in the metropolitan Detroit area.

In 2016, in the three counties with the largest proportion of black voters — Wayne, which contains Detroit; Genesee, which contains Flint; and Saginaw, which Trump flipped red for the first time since 1984 — Clinton beat Trump by about 143,000 fewer voters than former President Barack Obama beat Mitt Romney in 2012. If she’d performed just marginally better among black voters there, strategists said, she would have won the state.

“You can’t make the same mistakes that Hillary Clinton made in 2016. You have to go to Michigan and talk to voters: auto workers, black voters, everyone,” said Terri Towner, a political science professor at Oakland University, just north of Detroit. She noted the pandemic makes that difficult.

At the moment, the polls look good for Biden. The latest RealClearPolitics polling average shows Biden leading Trump 46.5 percent to 42.3 percent in Michigan, fueled by underwater approval ratings for Trump in the state.

“It’s Joe Biden’s election to lose in Michigan,” said Bill Ballenger, a political radio talk show host and a former Republican state lawmaker. “But he could easily lose it. He is just not that strong of a candidate.”

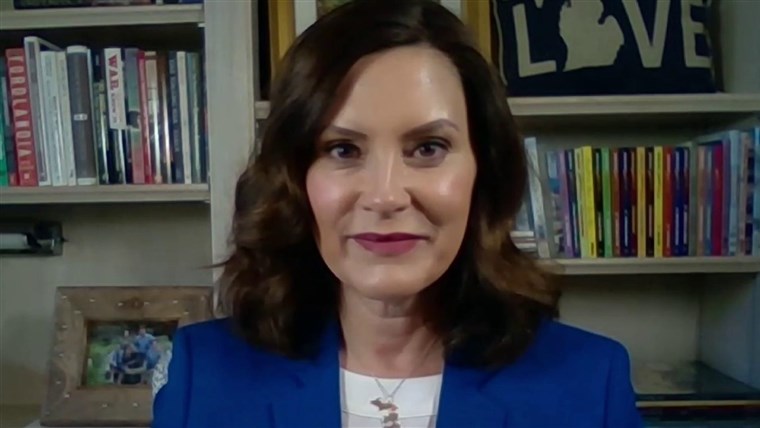

The robust protests against the stay-at-home orders implemented by Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (who has been mentioned as a possible Biden running mate) exposed both the anger and frustration held by many voters outside the metropolitan Detroit area for the economic restrictions imposed on them, as well as a persistent support level among Trump’s base. While Trump tweeted in support of the protesters, strategists and people on the ground in Michigan said a lot of the turnout for those demonstrations was organic — which could possibly foreshadow heavy turnout for Trump in the fall.

Another bad sign for Biden is how he’s faring in Macomb County, a working-class county north of Detroit that political scientists point to as the ultimate bellwether for the whole state. (George W. Bush carried it in 2004, Obama carried it twice and Trump won it in 2016.) Macomb County voters, as well as Michigan strategists and political scientists NBC News interviewed, say it seems destined to go for Trump again.

“Joe Biden is an empty suit,” said Michael Cojanu, a 53-year-old furniture store employee who lives in Sterling Heights, in Macomb County. “Liberals have grown too nasty,” added Cojanu, who voted for Obama in 2008, Romney in 2012 and Trump in 2016.

Another warning sign: The Trump campaign has put its foot on the gas in Michigan.

Trump Victory, the joint operation between the Trump re-election campaign and the Republican National Committee, said that despite the outbreak, it has made nearly 2.2 million voter contacts online in the state and has held nearly 350 virtual training sessions with more than 2,000 volunteers since March 13, when the campaign went all-digital. The campaign also has more than 50 paid staffers on the ground throughout the state.

Campaign officials repeatedly pointed to a visit Trump made to a Ford production plant in the state last month — criticized as nonessential amid the ongoing pandemic — as evidence the president would be working hard to keep the state red. Additional future visits are likely, said Trump Victory spokesperson Rick Gorka.

Democratic strategists and the Biden campaign, however, pointed out that Biden won every county in Michigan in the state’s March 10, pre-lockdown Democratic primary — a tour de force they said demonstrates strong voter enthusiasm for him.

They also pointed to how strongly Biden performed among African American voters in the earlier primary states, despite running a bare-bones campaign in many of those states, and Michigan’s 2-year-old law that allows any voter to cast an absentee ballot. Those developments have led many to believe Biden will prevail in the general election, despite a campaign that will be hampered by the pandemic.

“He has a history of having been in charge of the auto rescue in the state. He has longstanding relationships in the state. And look what Joe Biden was able to do with African American voters in a very competitive Democratic primary,” said Dan Lijana, a Michigan-based political and communications consultant.

In the meantime, the Biden campaign has put a heavy emphasis on virtual events targeting Michiganders. According to the campaign, Biden and his wife, Jill Biden, held a combined six virtual events with Michigan politicians or voters in May. Biden has also leaned into frequent appearances on local media in recent weeks, emphasizing a message of unity and empathy.

The campaign, however, declined to say how many paid staffers it had on the ground in the state and how many voters it had reached virtually since the campaign went all-digital.

That has raised some red flags among Democratic voters and activists, with many pressing Biden to set foot in Michigan, the way Trump did recently.

While Lemmons and Small lauded Biden’s speech on Floyd’s death earlier this week and expressed confidence he would win the state, Lemmons emphasized that the stakes, especially for black voters, are way too high for his campaign to not do everything it can.

“They’ve got to get creative and have some semblance of in-person meetings with folks here,” he said. “They just can’t leave it to chance.”