ATLANTA — The pin was small, and rusted on the back. Sharon Wood had packed it away in 1973 as a relic of a battle fought and won: the image of a black coat hanger, slashed out by a red line.

Then this spring, her home state, Georgia, joined a cascade of states outlawing abortion at the earliest stages of pregnancy. Ms. Wood did what she never imagined she would need to do again. She dug it out, and pinned it on.

“Don’t ask me how it all happened,” Ms. Wood, 70, a retired social worker northeast of Atlanta, said one Sunday afternoon, the pin on her dress. “I know so many people who said they woke up when Trump was elected. Well, they shouldn’t have been asleep.”

For years, abortion rights supporters like Ms. Wood believed the 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court ruling had delivered their ultimate goal, the right to reproductive choice. Now, they are grappling with a new reality: Nationwide access to abortion is more vulnerable than it has been in decades.

In a six-month period this year, states across the South and Midwest passed 58 abortion restrictions. Alabama banned the procedure almost entirely. Lawmakers in Ohio introduced a similar bill shortly before Thanksgiving. And in March, the Supreme Court will hear its first major abortion case since President Trump added two conservative justices and shifted the court to the right; how it rules could reshape the constitutional principles governing abortion rights.

For abortion opponents, this moment of ascendancy was years in the making. Set back on their heels when President Barack Obama took office, they started methodically working from the ground up. They focused on delivering state legislatures and gerrymandered districts into Republican control. They passed abortion restrictions in red states and pushed for conservative judges to protect them.

And then unexpectedly, and serendipitously, Mr. Trump won the White House. Ending legal abortion appeared within their reach.

As Planned Parenthood and its progressive allies have rallied the resistance, the shift in fortunes in the abortion wars has been mostly attributed to the right’s well-executed game plan. Less attention has been paid to the left’s role in its own loss of power.

But interviews with more than 50 reproductive rights leaders, clinic directors, political strategists and activists over the past three months reveal a fragmented movement facing longstanding divisions — cultural, financial and political. Many said that abortion rights advocates and leading reproductive rights groups had made several crucial miscalculations that have put them on the defensive.

“It’s really, really complicated and somewhat controversial where the pro-choice movement lost,” said Johanna Schoen, a professor at Rutgers University who has studied the history of abortion.

National leaders became overly reliant on the protections granted by a Democratic presidency under Mr. Obama and a relatively balanced Supreme Court, critics say, leading to overconfidence that their goals were not seriously threatened. Their expectation that Mr. Trump would lose led them to forgo battles they now wish they had fought harder, like Judge Merrick B. Garland’s failed nomination to the bench.

Local activists in states like Alabama, Georgia, North Dakota and Missouri where abortion was under siege say national leaders lost touch with the ways that access to abortion was eroding in Republican strongholds.

“Looking at the prior presidential administration, there was a perception that everything is fine,” said Kwajelyn Jackson, the executive director of the Feminist Women’s Health Center, an independent clinic in Atlanta that has provided abortions since 1976. “We were screaming at the top of our lungs, everything is not fine, please pay attention.”

Discord at Planned Parenthood, the nation’s largest and most influential abortion provider, exacerbated the problem. In July the group’s new president, Dr. Leana Wen, was forced out in a messy departure highlighting deep internal division over her management style and how much emphasis to place on the political fight for abortion rights.

Planned Parenthood’s acting head, Alexis McGill Johnson, said that Mr. Trump’s election, new abortion restrictions and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court provided a wake-up call to many national leaders, including herself, that forced them to confront the entrenched challenges of class dividing their movement.

“A lot of us are awakening to the fact that if you are wealthy, if you live in the New York ZIP code or California ZIP code or Illinois ZIP code, your ability to access reproductive health care is not in jeopardy in the same way that it is in other states,” Ms. McGill Johnson said in an interview.

Ask Our Reporters

Our reporters are available to answer a selection of readers’ questions on the battle over abortion and their reporting. Please submit your question below.

New to The Times? Create a free account

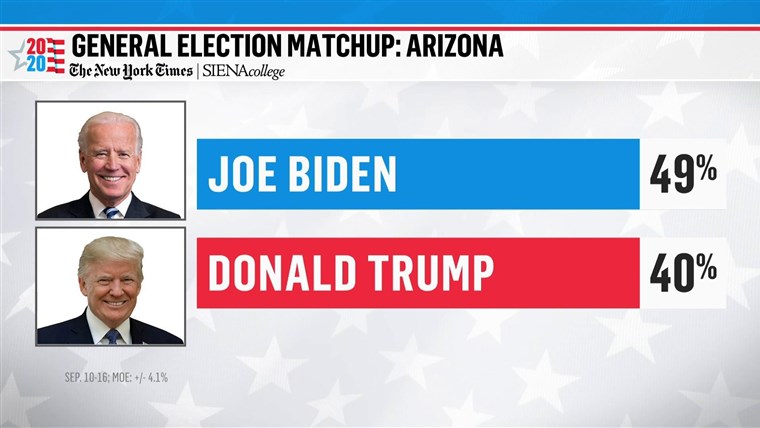

The right is pouncing on this moment of tumult, threatening to wield abortion politics to its favor in the 2020 presidential race. A leading anti-abortion political group, the Susan B. Anthony List, has more than doubled its campaign budget, from $18 million in 2016 to $41 million this cycle. Its goal is to reach four million voters, up from 1.2 million in 2016. The group says surveys it has conducted in swing states like Arizona and North Carolina show that portraying Democrats as supporters of infanticide — an allegation the left says is patently false — can win neutral voters to their side.

“They have fallen from that pinnacle of power to this,” Penny Nance, president of the Concerned Women for America, a conservative group that opposes abortion, said of the abortion rights movement.

“I hope they continue doing what they are doing,” she said of the left’s political strategy. “We’ll run the table in 2020.”

On the campaign trail, national Democrats have responded by making unqualified support for abortion a litmus test to shore up a progressive base, boxing in moderate candidates in red states and leaving little room for the complex views on the issue that most Americans hold.

In June, when Joseph R. Biden Jr. reaffirmed his decades-long support for the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits federal funding for abortions, he was harshly criticized by supporters of abortion rights, including from within his own campaign; within a day he had changed his stance. In November, the Democratic Attorneys General Association announced it would support only candidates who support abortion rights and access.

Amid the high political maneuvering, there are fundamental internal divisions that the abortion rights movement has not resolved, especially between Planned Parenthood and the independent clinics that perform most abortion procedures.

This past summer, for instance, after Alabama passed its near-total abortion ban, celebrities and liberal donors opened their checkbooks en masse to support Planned Parenthood. The founder of Tumblr gave $1 million. The pop star Ariana Grande held a benefit concert.

At the same time, Gloria Gray, who heads the West Alabama Women’s Center in Tuscaloosa, said she couldn’t afford to give her staff raises or pay for a $20,000 fence to keep the daily protesters off the property. Her crowdfunding effort produced about $4,000.

Ms. Gray’s clinic performed about 3,300 abortions last year, more than half of all the procedures in Alabama. Planned Parenthood’s two clinics performed none.

“With the national organizations,” she said, “we seem to be left out.”

The cultural and financial disconnect between regional clinics and national leaders in the abortion rights movement has been brewing for years. Tammi Kromenaker, who runs the only remaining abortion clinic in North Dakota, said she saw the national crisis coming in 2013, when North Dakota became the first state to enact a ban on abortion after six weeks of pregnancy.

At an annual working group meeting with abortion rights leaders — “folks from the coasts,” she recalled — the conversation centered not on the challenges to abortion rights in her state but on whether artwork conveying female power in a New York clinic’s waiting area was too provocative and would alienate its changing patient base.

A short time later at a different annual meeting, an activist from California suggested North Dakota advocates should have had a better messaging strategy to prevent the ban. “You don’t think we have the right message?” Ms. Kromenaker remembered in exasperation. “We have given every message.”

“They are never threatened, so they never have to think the way we do,” she said, referring to national leaders.

Independent clinics like Ms. Kromenaker’s and Ms. Gray’s in Alabama — unaffiliated with Planned Parenthood — perform about 60 percent of the country’s abortion procedures, according to groups that track the data. Those clinics have essentially no lobbying or political power.

Few state activists want to question Planned Parenthood or its strategy publicly, especially when they are allies in court and some receive financial support from the national organization. Planned Parenthood affiliates, with counsel like the American Civil Liberties Union, have sued to block the restrictions this year in eight states, offering legal muscle many independent clinics cannot provide for themselves. Some laws have been temporarily blocked from going into effect in the lower courts, though they could end up being decided by the Supreme Court.

Many people interviewed acknowledged the unique pressures Planned Parenthood faced, especially as conservative activists made defunding the group a top policy objective in recent years.

Ilyse Hogue, president of the abortion rights organization NARAL Pro-Choice America, said that independent clinics “absolutely” needed to be better funded, but that ultimately protecting the clinics depended on bigger changes.

“I don’t think they will be able to continue to operate at all if you don’t shift the culture and politics,” she said. “The trajectory we are on will outlaw service.”

Still, some worry that Planned Parenthood and other national groups have overly prioritized politics and power instead of patients and providers. Though Planned Parenthood is perhaps best known as the nation’s largest abortion provider, it provides a range of health services across more than 600 centers across the country, including contraception; testing for sexually transmitted infections; and hormone therapy for transgender patients.

The tension between Planned Parenthood’s political goals and its mission as a health provider was one of the main reasons Dr. Wen, with a background as a physician, had such a stormy tenure as president.

Pamela Merritt, who co-founded a reproductive rights group called Reproaction in 2015, compared Planned Parenthood’s legal priorities to a lobbyist for a commercial enterprise like McDonald’s, focused on protecting its own business needs. Activists refer to the organization and its outsize influence, she said, as “the big pink elephant in the room.”

“The movement needs independent providers that provide most abortions to be loud and out front,” said Ms. Merritt, who described herself as an “unapologetic lefty.”

For many of those independent providers, the problem extends well beyond politics.

In Alabama, Ms. Gray’s biggest challenges are practical. Drug prices for medical abortions are high, she can’t find a physician to replace her aging medical director, and an electrician recently refused services because he opposed abortion, she said.

Amid these pressures her client base has grown, especially because Planned Parenthood has not provided abortions in Alabama since March 2017, according to state department of heath data, though it advertised the service. Critics say that Planned Parenthood has been more focused on using the political climate in Alabama to raise money than on providing health care services.

After multiple inquiries over several weeks from The New York Times about when and why Planned Parenthood clinics stopped providing abortions in Alabama, the regional affiliate president, Staci Fox, said the group planned to resume providing abortions later this year. The group also removed web pages advertising the procedure in Birmingham and Mobile.

Planned Parenthood health centers are all 501(c)(3) nonprofits, but 85 percent of independent clinics are not, according to the Abortion Care Network, the national association for community-based abortion providers, which has 13 staff members and no political advocacy arm. Clinics like Ms. Gray’s are for-profit businesses that rely on payments for services to stay open.

The financial challenges are daunting. In Arizona, independent clinic leaders are expanding the Abortion Fund of Arizona, a NARAL project that provides direct assistance to abortion patients; it has received about $50,000 in donations this year, said Donna Matthews, the fund’s treasurer. In Arkansas, the Little Rock Family Planning Services, a small for-profit that offers the only surgical abortion services in the state, received a $30,000 grant from the National Women’s Law Center.

Ms. McGill Johnson of Planned Parenthood pushed back against criticism that her group was inattentive to the needs of small abortion providers. The broader reproductive rights ecosystem, she said, was crucial. “We recognize that Planned Parenthood is one small piece of the work to defend access,” she said.

“Pitting us against each other makes it impossible to provide health care,” Ms. McGill Johnson added. “The only way we survive is by building the strongest network possible.”

Still, the fragmentation in the movement has persisted. In Alabama, that was evident in the growing popularity of the Yellowhammer Fund, a nonprofit started in 2017 that covers medical, travel and other costs for low-income abortion patients. After Alabama’s ban was enacted, prominent national groups like Planned Parenthood and NARAL, as well Democratic presidential candidates like Senator Bernie Sanders, rushed to support the group.

The Yellowhammer Fund raised $4 million in 10 weeks, and its director, Amanda Reyes, said about $500,000 was budgeted to cover abortion procedures. Ms. Gray and the two other independent clinic directors in the state had hoped more resources would be directed to meet their needs. But Ms. Reyes has put forth a different vision to address broader challenges that women of color and low-income families might face, like access to financial and health care resources to care for additional children.

Yellowhammer is planning to support other aspects of reproductive rights, like doula care, she said, and hopes to build new “reproductive justice centers” designed to compete with anti-abortion pregnancy centers by providing things like diapers and pregnancy tests.

Their efforts are a sign that the left knows it needs new strategies, but also of the wide disagreement over what they should be. In describing her vision, Ms. Reyes used language some say is similar to the rhetoric frequently deployed by abortion rights’ fiercest opponents.

“If all we do as an organization is pay for abortions for low-income people, we are eugenicists,” Ms. Reyes said. “That is not transformational work. That is slapping a Band-Aid on a huge problem.”

At a NARAL town hall event with Bernie Sanders this summer, Karina Chávez rallied a crowd in a Des Moines ballroom by describing how she had an abortion at age 14. The father, her boyfriend, would become a drug addict, and her Catholic parents fiercely opposed abortion. The procedure itself, she said, was the easier part.

“Making a decision about your reproductive health doesn’t need to be a traumatic life experience,” Ms. Chavez, a Sanders supporter, told several hundred voters.

Her position reflects a wing of the reproductive rights movement that encourages women to “Shout your abortion,” and that believes building cultural support for the procedure depends on destigmatizing it.

“Going moderate, it is not a winning strategy,” said Jessica González-Rojas, who leads the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health.

Politically, that means mirroring the right’s successful tactic of doubling down on a firm position — and using energy from the liberal base instead of building bipartisan, cultural support.

This has led to close alignment with the Democratic Party. In recent years, Planned Parenthood has become one of the biggest sources of volunteer power for Democratic campaigns. In 2018, the group’s political arm gave more than $1.1 million to Democrats and just $5,735 to Republicans, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.

The Democratic Party has rejected the message that drove its politics since President Bill Clinton’s administration — that abortion should be “safe, legal and rare” — and embraced abortion rights with few stipulations. Every leading Democratic presidential candidate has fallen in line.

But unlike support for same-sex marriage, which rose drastically before it was legalized nationwide, Americans’ views on abortion have remained relatively consistent since 1975. A majority of Americans believe the procedure should be legal — but only in certain cases, according to Gallup’s long-running tracking poll.

Some abortion rights supporters worry that establishing abortion rights as a Democratic litmus test is too inflexible for Americans conflicted over abortion. They fear that it could hurt the party in rural areas and the more moderate, suburban districts that may hold the key to regaining the White House, and where many of the remaining vulnerable abortion clinics are.

Only five Democrats who oppose abortion rights remain in Congress, according to congressional votes tracked by NARAL, and at least two are facing primary challenges from women who have made support for abortion rights a key part of their campaign. In Louisiana, Gov. John Bel Edwards, a rare Democratic officeholder in the South, won re-election last month after campaigning on his support for a state law banning abortion after about six weeks of pregnancy.

J.D. Scholten, a Democrat running to replace Representative Steve King, an Iowa Republican, said that about 60 percent of voters in his culturally conservative district considered themselves “pro-life.”

“Where I’m from, we have a pretty big tent,” he said. “We can’t be writing off people. I need all the votes I can get.”

But many activists dispute the notion that compromise with abortion opponents constitutes a success. Appealing to the middle prioritizes the views of white moderates at the expense of the health care needs of women of color, critics like Ms. Merritt of Reproaction say.

“You have to change the structures,” she said. “We have ceded ground we didn’t need to about the power of our ideas.”

Cecile Richards, the former president of Planned Parenthood and the woman most associated with the reproductive rights movement under President Obama, has shifted her efforts and formed a new organization, Supermajority, that casts abortion as part of a wide range of issues affecting women.

Over a breakfast of eggs and biscuits in Birmingham, Ms. Richards and two of her co-founders said they saw an opening to talk about female empowerment instead of narrower debates like when pregnancy termination should be allowed. That means building an interracial alliance with activists working on issues like immigration, economic justice and gender equality.

“Look, movements ebb and flow, it does not mean that movement was a failure,” Ms. Richards said. “We can learn things from the past, and we can also do things differently.”

All of these efforts will be tested in the coming months, as both parties move into the pressure cooker of a general election and a series of court battles, where abortion politics will be front and center. For Ms. Wood, the woman with the rusted pin, the conflict feels familiar.

As she waited for the kickoff event of the Supermajority tour, she compared the moment to the pre-Roe years. Abortion rights advocates must rebuild their grass-roots power, she said, or risk suffering the consequences.

“I’ve stayed politically active,” Ms. Wood said as she stood in the half-empty hall. “But without a movement around you, it’s hard to feel empowered.”