In a politically divided nation, with attitudes among many voters hardened and resistant to changing, the 2020 general election could be contested on the narrowest electoral terrain in recent memory.

Just four states are likely to determine the outcome in 2020. Each flipped to the Republicans in 2016, but President Trump won each by only a percentage point or less. The four are Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin and Florida. Many analysts point to Wisconsin as the single state upon which the election could turn.

Shifting demographics, the growing urban-rural divide and the gap between white voters with and without college educations have helped to create an electoral map unlike those of the recent past. So too have Trump’s unique profile, messaging and appeal.

“Because of the partisanship of the country and the partisanship of the president, we are now looking at the smallest map in modern political history,” said Jim Messina, who was the campaign manager for former president Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign.

Both Trump’s campaign and that of his eventual Democratic challenger will seek to put other states in play. But those opportunities are fewer than in past campaigns.

Trump has done nothing to expand his base while in office, which Democrats claim will make it extremely difficult for him to win states he lost in 2016. Trump campaign officials disagree. Democrats’ aspirations for expansion rest in part on whether politically changing, Republican-held states such as North Carolina, Georgia and Arizona are truly ready to shift.

Current polling nationally and in some of the key states shows the president vulnerable when matched against several of the Democratic presidential candidates — though he overcame weak approval and favorability ratings to win the 2016 election. Based on current attitudes, he will have to do so again to win reelection.

One obvious wild card is the identity of the Democratic nominee and how that shapes the general election debate. Will that nominee be running on a platform that moderate voters see as too far left? Will that nominee be able to energize the party’s woke base and still appeal to white working-class voters?

Regardless of who that person is, the 2020 election will put a focus on several demographic groups in particular.

First, white working-class voters who went strongly for Trump and are an important part of the GOP’s base. Of particular concern for the president will be white women without college degrees.

Second, college-educated suburban voters, especially women, who have moved decisively into the Democrats’ coalition and who powered the party’s gains in 2018 House races.

Third, African Americans, and particularly younger African Americans, whose turnout levels will be critical to Democrats’ fortunes.

Fourth, Hispanic voters, who will play a key role in Florida and some other states, especially in the West.

How strongly each of these groups supports Trump or the Democratic nominee and the numbers by which they turn out to vote are variables that election modelers are analyzing closely and tweaking regularly even at this early stage.

The math of 2020

In 2016, Trump lost the popular vote to Clinton by roughly three million people but won 304 electoral votes and the presidency. Based on current polling, his chances of winning the popular vote are at least as challenging as in 2016, leaving open the question of whether he can again produce an electoral college majority.

The electoral college combinations all begin with Florida and then move to the upper Midwest. One scenario not out of the realm of possibility would produce a 270-268 victory for Trump, but only if he again secures one of Maine’s four electoral votes.

If Trump were to win Florida again, Democrats would need to recapture all three of the northern states — or find substitutes — to win the White House. If Democrats could win Florida, any one of the three in the upper Midwest would give them the White House, unless Trump can put something else in his column.

The three northern states were part of a group of 18 states and the District that had voted for the Democratic nominee in every election between 1992 and 2012, what Democrats believed constituted a “blue wall” of resistance to repeated incursions by Republican nominees.

Trump broke through that wall, threading the narrowest of paths to victory. His combined margin in those three states, however, was just 78,000 votes out of nearly 14 million cast.

Election analyst Ruy Teixeira said the three states were so closely decided that even small changes could shift them to the Democrats, from the demographic changes taking place since the 2016 election to a white voting block that is moving away from Republicans or even to modest increases in turnout in the minority community.

“There are a lot of knobs you could twist and you don’t have to twist them very far to move them into the Democrats’ column,” he said. For Trump, that means there is an “absolute necessity” to maintain and likely to increase his margins among white, non-college voters next year.

While many Democrats are optimistic that the gains in the 2018 midterms foreshadow success in 2020, a report earlier this year by the progressive firm Catalist noted, “It is not safe to assume that Democratic gains from 2016 to 2018 will hold.”

A changing electoral map

In past campaigns, when there were a dozen or more truly competitive battlegrounds, presidential nominees could chart multiple paths to 270 electoral votes and worked to keep as many of those options alive as long as possible.

Over many years, however, growing polarization has created red and blue strongholds, with bigger and bigger and bigger victory margins. In 2016, with a narrow popular vote margin, more than two dozen states were decided by margins of 15 points or more. In 1988, when the popular vote margin was seven points, there were just 17.

The electoral map is never truly static for long. Before the Democrats’ “blue wall” there was the so-called “Republican lock” on the electoral college. Years ago, California, Illinois and New Jersey were presidential battlegrounds. Today all are solidly Democratic. Missouri long was considered a bellwether state. Trump won it by almost 19 points.

One way of looking at how the electoral map has changed in recent years is to gauge which states are most likely to provide the final votes needed to hit the necessary 270. During the two elections won by Obama, Virginia and Colorado were perched at that tipping point. Today, because of Democratic gains among college-educated voters, both have moved significantly toward the Democrats.

One of the most significant changes in the 2020 map is the reduced role Ohio will play in the calculations of the campaigns. Underlying trends have moved Ohio toward the Republicans in statewide races, and Trump’s candidacy provided an extra boost.

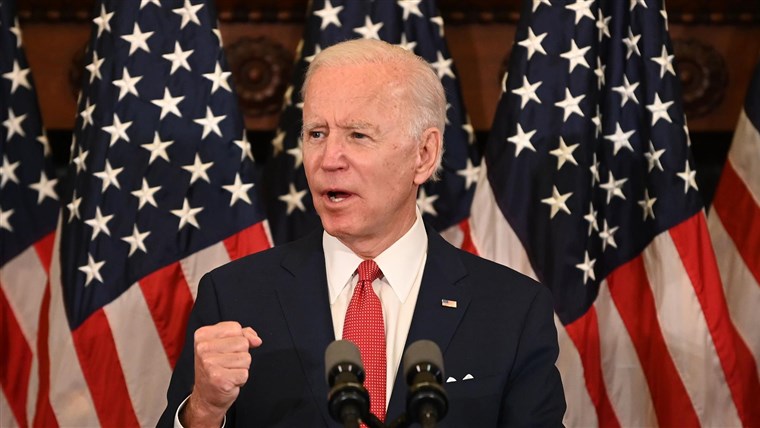

Democrats say they will not ignore the state, though how much they invest there is questionable. A Quinnipiac survey in June showed former vice president Joe Biden leading Trump in Ohio by eight points. If the president is trailing in Ohio by that margin in the late fall of 2020, his reelection prospects likely would be doomed.

Iowa is another example of how Trump’s appeal to rural areas and to older, predominantly white voters has changed the electoral map. No state in the country saw as many counties that had voted for Democratic nominees in five or more elections consecutively switch allegiance and support Trump.

Trump won the state by nine points in 2016, and strategists in both parties see it as less competitive than other places. But the president’s tariffs have hit the Midwest farmers hard. If they are feeling pain next year, Trump’s hold on Iowa could be at risk.

The big four states

Florida has been ground zero in presidential politics for two decades. George W. Bush won it by 537 votes in the disputed election of 2000. Obama carried it by a fraction of a percentage point in 2012. Trump won it by slightly more than a percentage point in 2016. In 2018, the gubernatorial and Senate races there were decided by margins of less than half a percentage point.

With 29 electoral votes at stake, Florida is the biggest competitive prize on the map. Neither Trump nor the Democratic nominee can afford not to invest the maximum there, though at this point, Trump appears to have a slight advantage.

Florida is also the most complex and costliest of the major battlegrounds, and for Trump, it is the most important state in the country. Trump’s team has divided the country into nine political regions. Only Florida constitutes its own region. Its importance was highlighted by the decision to open the president’s reelection campaign with a rally in Orlando.

Both sides know what they need to do in Florida. Compared with some other states, Florida’s electorate is not just narrowly divided but also relatively inelastic. Unlike some other states, where Trump’s candidacy produced different regional margins from past elections, voting patterns in Florida more closely followed those of 2012. Unlike the northern states, Florida was a state where both Trump and Clinton got more votes than Mitt Romney and Obama in 2012. For 2020, the issue will become who comes out to vote.

Of the northern states, Trump won Michigan by the fewest number of votes, just 11,000. Between 2012 and 2016, the Democratic vote badly eroded, with Clinton falling about 300,000 votes short of Obama’s total, including about 75,000 fewer in Wayne County, which is home to Detroit.

Bitterness lingers among Democrats in Michigan over the 2016 campaign and how it was played by Clinton’s team. The 2018 midterms since have given Democrats some cause for optimism. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer recaptured the governor’s mansion and the party picked up two congressional districts.

Democrats made gains among white, working-class voters who had broken to Trump in 2016, but also added votes in areas where Clinton had done better than Obama. Matt Grossmann, director of the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research at Michigan State University, said that poses a question about the strategy for 2020.

“Is the better hope of returning some traditional Democrats back into the fold or continuing to make gains among highly educated voters that were more traditionally Republican?” he said.

The Democrats’ formula for success once followed Interstate 75 north from Detroit through Pontiac and Flint to Saginaw. But declining populations have hurt the Democrats.

“With lower populations in Detroit and Flint, that is not enough of a winning coalition,” said Amy Chapman, a veteran Democratic strategist in the state.

Macomb County, birthplace of the Reagan Democrats, still draws attention but is not as important to Democrats as nearby Oakland County, a once-Republican stronghold that has moved significantly toward the Democrats.

Democrats also have opportunities in some outstate areas. Kent County, home to Grand Rapids, is one area of Democratic growth. Other prospects include higher-educated counties such as Grand Traverse along Lake Michigan and Midland in the center of the state.

Richard Czuba, a Michigan-based independent pollster, said the biggest threat to Trump is the prospect of increased Democratic turnout. Trump got about the normal number of votes that past Republican candidates have received; Clinton was significantly below not just Obama but other Democrats. Though both sides are highly motivated, Czuba said, “The only upside in an increased turnout is for the Democrats.”

Pennsylvania presents another challenge for Trump and for the Democrats. Clinton was criticized for her campaign’s failure to pay more attention to Michigan and Wisconsin, but that was not an issue in Pennsylvania, where she campaigned constantly and invested heavily.

The results reflect the difference. Clinton held her own in Philadelphia and its suburbs, winning the Philadelphia media market by about 25 points, roughly the same as Obama in 2012, according to analysis by Clinton strategists. But Trump swamped her in other parts of the state. In the Scranton market, Obama lost by about 4 points, Clinton by 25. In the Johnstown area, Obama lost by 25 points, Clinton by 37. In Democratic Erie, which Obama won by 5 points, Clinton lost by 13.

G. Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, said he doesn’t rule out another Trump victory in the state.

“But to do it he’s got to win those rural and small towns with significant turnout and/or find a way not to lose the Philly ’burbs by a larger percentage than [against Hillary],” he said.

David Urban, a political adviser to the president and his campaign, predicted that Trump voters will be out in force but added, “The president put a lot of time and effort into Pennsylvania [in 2016] and it paid off. This time in 2020 he’ll do the same, but he’s going to have to put a little more effort into Pennsylvania because Democrats who took him for granted in 2016 will not be taking him for granted in 2020.”

Former Democratic governor Ed Rendell said he would watch five counties as clues to 2020: Delaware and Bucks in the Philadelphia suburbs; Luzerne, home to Wilkes-Barre and long a Democratic county; Cambria, home to Johnstown; and Clinton, home to Lock Haven. But he said he was bullish about 2020 because he expects voters who seemed to abandon Clinton at the end will be back in force.

That leaves Wisconsin, where Democrats will hold their convention next summer, as potentially the most competitive of the three. Wisconsin is seen as more difficult for the Democrats than Michigan or Pennsylvania because it has a higher percentage of white voters overall, particularly of white non-college voters, and because the Democratic infrastructure was weakened during former Republican governor Scott Walker’s eight years in office.

Wisconsin has seen a notable shift in voting patterns over the past decade, changes that Trump accelerated in 2016. As Craig Gilbert of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel wrote shortly after the 2018 elections, “Most Wisconsin voters live in places that are trending in one political direction or the other. But the state persists as a partisan battleground because all those regional shifts over the past two decades have somehow canceled each other out.”

Northwestern Wisconsin has become more deeply entrenched as Republican territory, while southeastern Wisconsin has become less friendly to the GOP. The city of Milwaukee and Dane County, home to Madison and the University of Wisconsin, remain the biggest and most important vote producers for the Democrats. Counties in the southwest and along the Mississippi shifted to Trump in 2016 but could move back to Democrats next year.

In 2016, Clinton suffered a falloff in the Milwaukee media market that was about double that of the state as a whole. Much of that erosion was concentrated in African American precincts in the city of Milwaukee. Combined with Trump’s big margins in the northwestern part of the state, that was enough to doom her chances.

Where Democrats see particular opportunities — and Republican see reasons to worry — are in three Republican counties in suburban Milwaukee: Waukesha, Ozaukee and Washington. Dubbed the “WOW counties,” all still favor Republicans, but Democrats have been gaining in their share of the vote.

“Those counties are still voting Republican, but as much as 16 points less on the margin now than they were,” said Charles Franklin, who conducts the Marquette University Law School poll.

Brian Reisinger, a Republican strategist, said the Democratic growth in those suburban areas in 2018 was “a real wake-up call for people to see there was a way for our traditional coalition to not be quite enough.”

Both sides approach Wisconsin nervously. Republicans see the dangers but are more unified behind the president than they were in 2016. Democrats elected a governor — Tony Evers — in 2018, but narrowly. Then they lost a state Supreme Court race in the spring that they expected to win.

“We underperformed,” said a veteran Democratic strategist who spoke on the condition of anonymity to be candid. “We have to get smarter about how we do our work.”

Expansion opportunities

The Trump campaign and Democratic strategists point to states beyond the big four as opportunities for flipping. The president’s political team has its sights on New Hampshire, which the president lost by less than half a point, as well as Minnesota, which he lost by only a point and a half.

Trump’s team also has said Nevada and New Mexico will be targets in 2020. Both present obstacles unless Trump can expand his electorates. Trump advisers also have mentioned Oregon as a possible target, though Democrats take that less seriously.

Trump advisers say that, as Democrats focus on picking a nominee, they have an opportunity to begin to build organizations in these kinds of states and to identify sporadic voters who are attracted to the president.

“We have the luxury of having the resources to protect the states President Trump won in 2016 and expand into states we think we can add to his column in 2020,” said Tim Murtaugh, the Trump campaign’s communications director.

Cornell Belcher, who was a pollster for Obama’s campaigns, said that, because of the changing status of some traditional battlegrounds such as Ohio and Iowa, it is more vital than ever for Democrats to compete hard elsewhere.

“Democrats have to expand the playing field and not put all our eggs in the basket of the traditional battleground states,” he said.

David Bergstein, the Democratic National Committee’s battleground states communication director, said the party is doing that even in the absence of a nominee.

“[We] are laying the groundwork now to ensure our eventual nominee has multiple pathways to 270 electoral votes,” he said.

Democrats see opportunities in North Carolina, despite losses there in 2012 and 2016, as well as Arizona and Georgia. Arizona, which Trump carried by just 3.5 percentage points, might prove to be a more attractive target for Democrats than either of the two southern states.

Some strategists see Arizona, with 11 electoral votes, as a possible hedge against a loss in Wisconsin, which has 10 electoral votes. In-migration from other western states and a growing Latino population have changed the political makeup of the state.

Public Opinion Strategies charted the ideological movement of Arizona voters earlier this year and found that the state today is only marginally more conservative than the nation as a whole, a significant change since 2010.

“The Arizona as you knew it is gone,” said Republican pollster Bill McInturff. But he added that Trump’s strong support among older white men and potential appeal to some Hispanic men could help to offset some of the movement in the state.

One state not likely to figure prominently into expansion possibilities for the Democrats is Texas. However attractive it might be as a state in transition, Texas would require an enormous investment. Democrats will play there only if everything else is moving in their direction.

Ted Mellnik contributed to this report.